Learn about the dangers of poetry, the lessons from collaboration, and the role of Ukrainian poets in this second part of our two-part interview with acclaimed poet, translator, and scholar Oksana Maksymchuk.

For part 1, click here.

This interview was conducted online on March 24, 2022.

I: Are there any poems that you have translated that had a lasting impact on you personally, maybe inspired you, and how so? Do you have any examples?

O: We’ve recently translated two books of poetry, recently meaning over the past three years. One is by Lyuba Yakimchuk, whom I just mentioned, that sort of avant-garde poetry. And another book is a book of voices by Marianna Kiyanovska called Voices of Babyn Yar. Babyn Yar is the place of the massacre of the Jewish population in Kyiv in 1941. Marianna started writing these poems during the war in Ukraine in 2014-15 and they came to her not as her own words, but as voices, mainly of children and women. She has a cognitive condition that makes it possible for her to hear voices, and to her, they appeared to be the voices of the dead. It’s a collection of around 56 poems that she selected out of 300 that she wrote over the course of maybe two or three months. They are little snippets of the witness experience, what it’s like to be that person in that specific place. It was a huge challenge to even undertake this project because of various ethical questions this strategy raises, but we did learn from this. She has this very bare transcript, there are no capital letters, no punctuation, or stanza breaks. At first, we introduced stanza breaks, a significant amount of punctuation, and some capitalization just to guide the reader where a sentence ends. But by the end of the project, we’ve pretty much decided to follow the author on most of these grammatical and typographical choices. That’s an example of being taught by her about how to convey this experience that she had of just being a transcriber and not a creator of this content.

Another example is working with Lyuba Yakimchuk’s poetry. At first, I also used a lot of periods at the end of lines. These are technical issues, I know that most people will not think forever about a comma, but poets do. I was inserting periods at the end of lines when I thought the sentence ended, but she said ‘No, for me the line break works as a natural pause, so you are just duplicating the effort.’ That was when she taught me something explicitly about how to transcribe her own poetry.

I took it to heart and then I started noticing how I had stopped using punctuation at line breaks in my own poems, too.

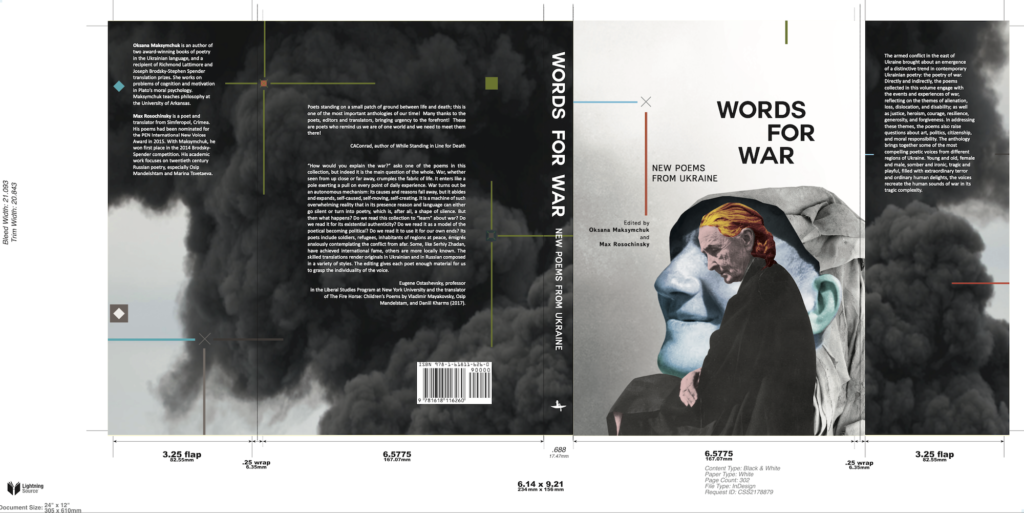

I: What did you learn from editing Words for War?

O: I’ve been thinking a lot about the project with Max, my husband, who is the co-editor and with whom we’ve been discussing not just the poetry that is represented within the anthology but also more broadly this phenomenon of war poetry that has been emerging in the past eight years.

One of the formulas that we came up with is that poetry is a form of soul-shaping and perspective-shifting technology.

It’s a sort of approach where, if used in a specific way, it not only helps you get into the person’s perspective but, as a poet, by the magic of a poem, I can immediately transport you to the position of another and make you feel for a moment what it’s like to be them. So, there is this idea of being in somebody’s shoes as the precondition for empathy but also, over the longer term, shaping who you think you are, what you value, what you’re after, what your dreams are, what is worth valuing and fearing – all of these things actually determine how you are going to live.

Now, as a soul-shaping technology, poetry can have a liberating effect, it can help people live more authentically, but it’s also what makes it a very useful tool for political propaganda. There can be various poems that harness this ability of poetry to tell you how to think and how to feel and use it for purposes that quite diverge from your own, individual ones. Because what we want as humans is to flourish as individuals, as communities. We don’t just want to survive at any cost, but we want to live well, and living well requires certain things that we have to figure out for ourselves. And it’s far from clear what it means to live a good life. But in the present moment, it seems that these conceptions of the good life have to involve not just other people but also the natural world, the animals, and the future of the planet. Their survival is a problem that we as individuals and as societies have an inherent interest in solving and addressing.

But a lot of this propaganda and political messages that we are getting diverts us from these broader goals and shifts our focus onto particular territorial fears of political actors who are pursuing their own, much more myopic projects of money and power that have little to do with us or our shared future.

That’s one of the dangers of some kinds of poetry. We did not include any such poems in our anthology. We tried to include the poems that are true, or ring true at least, against the fake news and the constantly updating Facebook feeds. But there is a lot of this kind of poetry and it’s worth looking at to understand how certain societies’ or individuals’ emotions, even though they seem to be in touch with themselves, have been crafted in such a way as to serve the needs and goals of figures that have nothing to do with their own ultimate purposes.

“Poets are not a lofty apolitical tribe whose only concern is their literary craft. Far from remaining blind to the world of strife and conflict they inhabit, they are often the ones most radically affected—and thus changed—by it.”

Excerpt from the preface of “Words for War” by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky

It’s true that poetry may seem innocent in various ways – it seems to say what it says and not to be pursuing any wider ideological agenda, but innocence is part of the craft. Unfortunately, there is a lot of poetry that has emerged that is serving political purposes rather than artistic purposes. There is no obligation for poems to not be art, right? They are artificial, they are not real-life phenomena, it’s just something we create. But on the other hand, we have a choice whether to create to serve humanistic purposes or to serve very specific temporally indexed purposes of political powers at play. And I think sometimes even the poets can’t distinguish a political perspective from their own. They get carried away as everyone else, there is a huge tradition of poets who have put their talent in the service of morally indiscriminate powers, of emperors, of colonizers, justifying and creating narratives that would support these processes. So, we have to keep that in mind, too, when we think about poetry as something that is necessarily free and liberating, that in fact, it can be a tool of enslavement, brainwashing, and false consciousness creation.

I: Collecting and editing this book and also looking at the current situation, what does it mean to be a poet? In the preface, you compare poets to fine-tuned machines registering ever-so-small changes and how that impacts them. What role does the use of language play as an outlet when it comes to reacting to those changes?

O: It’s this very widespread comparison of a poet to a barometer. It’s a measuring device that converts air pressure into a recognizable numerical value. I wasn’t aware of that metaphor before we wrote the preface, but then Ilya Kaminsky wrote his introduction and he made it very clear that it’s a widely used metaphor for explaining what poets are and why they are so effective at conveying these immediate barely registered shifts in how language is used and how meaning is created. I think it’s a good one, because poets work with language and emotions, not just shaping but reflecting them. This is why they are so good at conveying the shifts in public and private perceptions about what kind of world we think we live in and what kind of world surrounds us.

But it’s not just registering what is given – the thing I said about the soul-shaping technology suggests this much more active and transformative role that a poet can play in the world, and poets do change the language. And in changing the language they also help us make sense of the new phenomena and of ourselves in this world that is changing so rapidly. So, in that transformative effect of poetry, I think, we can hope for a certain kind of healing to take place, because it’s not just words. It’s also the creation of certain images that can make us perceive our experiences in a new light and find meaning and healing in them. Whereas if we encounter them without the help of these words and images that the poets are providing us with, then what we encounter is just heaps of garbage, rubble, and inanimate objects that we cannot sort through ourselves.

So a lot of this transformation is actually making something out of what is broken, destroyed, the apparent garbage. Trying to create a new sense of stability, a new sense of identity, not just individual but also collective, out of the rubble that we find ourselves confronted with on the level of images – the broken promises, the words that no longer make sense, things that get repeated to the extent that we no longer believe in them, just the sheer numbers of the dead and the injured and the displaced. All of these things require some additional work, and poets, I think, help us do some of that work to heal, bear witness, and come to terms with their reality.

“In this, poets resemble well-crafted and finely tuned devices that register the relevant fluctuations with greater precision than the rest of us do. Because they work with language, it seems to happen almost automatically, involving little conscious reflection: the change in inputs simply leads to a change in outputs.”

Excerpt from the preface of “Words for War” by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky

I: You already touched upon the significance of poets in times like these. But what do you personally wish your readers to take away from reading your poetry?

O: I personally, as a poet, don’t see any one thing, any one result that I want to produce. I think that what interests us when we read poetry is precisely to gain self knowledge. Everything that we do in this domain is a quest not just to have another experience – like when we listen to music maybe we want to be overcome by a particular kind of feeling or be intellectually engaged by a particular harmony or coordination of sounds that we are experiencing. I think in reading poetry we often don’t just want to travel to a new place or get to know someone or something new, but to have a deeper experience of ourselves, to be taught how to know ourselves and how to feel within our own perspectives.

The poetry that I have been writing in recent weeks has not been about how to heal or overcome the pain but rather about how to feel numb. And that’s because I think many people don’t know what it’s like to have been affected by war. So it’s not really directed to the people who are having this experience, they will know exactly what I’m talking about or what the poems are trying to do. It’s rather to change the perspective of those people who haven’t had these experiences, so that they feel something like an echo of an experience that the people they are sharing the world with have had on a massive scale in recent weeks. You may once again say that this is not a pleasant thing that we should somehow be seeking out, but I do think that feeling numb in the face of war is another aspect of the experience that does help you gain deeper self-knowledge. Just as the Greeks had particular faith in the connection between suffering and truth – that truth is revealed through suffering, and it’s not exactly clear what truth that is, but it has something to do with the boundaries of the self and what it’s worth to live for.

So, I think in these moments it’s really important to affirm life, to feel joy, to revive our sensations if you are somebody who has been numbed by war. But for people who haven’t, I think it’s equally important to bring them to the other end of the spectrum.

On a more positive note, what I’m hoping is that it might help someone who is experiencing the poem to feel deeper joy and affirm life more intensely than they have before. Because many of the things we come to know in our lives we learn through experiencing contrast or change.

I: Where do you see yourself going with your work and writing? Do you have specific plans in mind or do you just go with the flow for now?

O: That’s the beauty of not having, for example, academic obligations at the moment – that I can do what I feel must be done in this specific moment and also something that only I can do, that other people cannot do for me. I feel that teaching philosophy courses, for instance, can very well be done by other people at the moment, but from my perspective, reflecting on the current situation is what I feel called to do. It’s true for any one of us that nobody can do our work quite the way we can. We are all unique, irreplaceable. So, in a way, maybe I’m saying that if you feel you need to process or work through something, poetry is one way of taking care of your subjective need.

To read more of Oksana’s work and stay updated on upcoming projects, find her website linked here.

For more information and a deeper insight into Words for War, check the recent BBC audio essay series on the book here.

Reviewed by Sarah Guvi, proofread by Anita Ghoreshi.

Header image by Natalya Mykhailychenko.