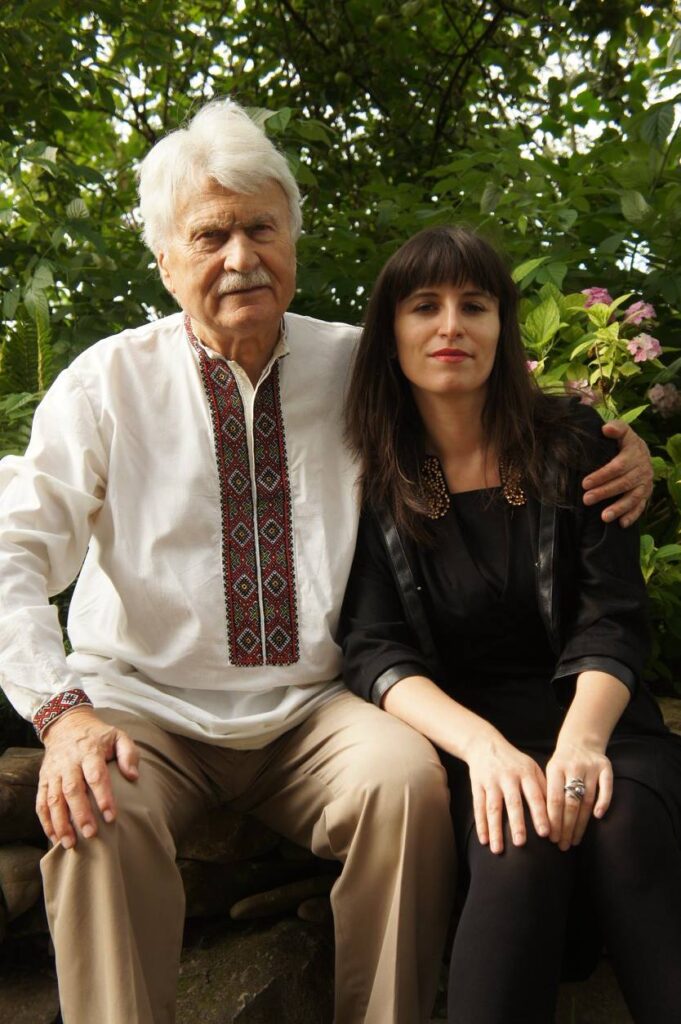

In this first part of our two-part interview with Oksana Maksymchuk, acclaimed poet, translator, and scholar, she talks about the power of poetry in times of war, the intricacies of language, and the important but impossible form of art that is translation.

She and her husband, Max Rosochinsky, along with Svetlana Lavochkina, translated a volume of poetry by Lyuba Yakimchuk, who recently performed at the 2022 Grammy Awards show, and published a collection of war poetry that includes Nobel Prize nominee Serhiy Zhadan’s work among many other memorable Ukrainian voices.

This interview was conducted online on March 24, 2022.

I: Can you tell us where you are right now? What’s your situation?

O: I am in Budapest. I was able to travel to Budapest right before the outbreak of the war with my husband and 10-year-old child. We have lived in Budapest before, so for us, it was a less disruptive transition than for many other families. We were both fellows at the Institute for Advanced Study at the Central European University which has also been displaced in recent years. But the institute stays in Budapest even though the rest of the university has been moved to Vienna. We’ve been able to find housing through the institute, in the building where we lived when we stayed in the city before. My son was able to go to the same school that he attended then, the REAL School Budapest. The school has been very active in helping other families who were similarly displaced, so they have about fifteen displaced refugee children enrolled through the end of the year and are thinking about how to continue that support program, hiring teachers, hiring child psychologists, hiring counselors who specialize in trauma to support the children and their families and the other children at the school who are now in this new situation welcoming children from this context.

The city we’re coming from, Lviv, is also considered relatively safe up until now. We have all been thinking that at some point if things go really bad it could get bombed, but so far it hasn’t been, while a lot of the other families that are arriving have lost their homes. They had been bombed out of their apartments, they lost all of their savings, all of their property, they have no homes to go back to. When you actually meet those people at the train station, as we sometimes do as volunteers, their experiences are vastly different and much more devastating than ours.

I: And what do you do as a volunteer?

O: Volunteers usually can do various things, they can bring food to the people who are arriving, they can translate and give directions. When we go, we usually translate, we direct people, and tell them how to get a ticket or how much the ticket costs – all of the tickets are subsidized depending on where they want to go –, we help them find their train. It’s all new information for them and many of them don’t know other languages. Even if they do know other languages, many have been traumatized. One of the after-effects of experiencing extreme stress is that you cannot access even the language knowledge you do have, so they’re stunned or overly excited, and it sometimes takes a special interpretive skill to get to them.

I: In addition to translating as a volunteer, you also write and translate poetry. How would you introduce yourself and the poetry that you’re writing to those who are not familiar with it?

O: My biggest project has been an anthology of contemporary Ukrainian war poetry. We – me and my husband, Max Rosochinsky – started working on this project in 2014 and it was published in 2017, so it took us a good three years to coordinate everything. I think in part because it was our first effort, and in part, because it was such a dynamic project seeing how everything was changing not only for the poets but also on the level of the language itself that the poets were trying to register. On the one hand, we developed this idea coming out of this feeling of helplessness that I think everybody is facing. We were in the U.S., experiencing the war from the distance, and we felt overwhelmed. Just consuming the news all the time seemed to further disempower us. It was perhaps motivated by this desire to heal ourselves, first and foremost, and to create this community wherein we could find a meaning and a purpose and a job for us to do, given our skills.

My husband is a Slavic philologist and I am trained as a historian of philosophy. I wrote my dissertation on Plato’s moral psychology, and he wrote his on Marina Tsvetaeva’s war poetry, so the project that seemed most natural to us involved poetry. We were finding a lot of really stunning, interesting poetry on Facebook, so that’s where we started looking and we eventually created this huge database of thousands of texts. So from that database, we eventually started selecting poems that somehow captured and crystallized some of these anxieties, fears, dreams, hopes, desires that emerged in this context of war. And based on that selection, we came up with our sixteen voices – the sixteen voices that are represented in the anthology. Eight of them male, eight of them female, discussing and reflecting on the war from very different perspectives.

We have a soldier-poet, we have a poet whose parents were refugees trapped in a city that she was having trouble getting them out of, in Luhansk. We have poets who were volunteers at the front, we have poets who were hosting refugees, we have poets who are reflecting on this process of watching the war just on the screen as it’s unfolding in a very self-conscious fashion – as observers or an audience to something that seems to unfold in the form of a spectacle, all of these very different interesting perspectives in Ukrainian and Russian.

After we had collected all of those poems, we found translators for them, so a lot of it was like matchmaking – the poets with the translators. And the interesting thing that happened is that many of these relationships actually survived the creation of the project itself. Some of these collaborations are ongoing, and in the current crisis, when pretty much everybody in Ukraine has lost their source of income or would have to be relocated, some of these translators are really stepping up and helping and supporting “their” poets. Not just in terms of trying to find them residencies but also financially, supporting them with work and funding.

I: How did you get into writing poetry?

O: I have this sort of pragmatic view about talent, about how one becomes talented at something. I think part of it is being gifted in terms of what you are willing and ready to pay attention to. But another part of it is exposure. I’ve been exposed to poetry from a very early age. My father is a professional reciter of poetry, an actor, and so I’ve been hearing poetry since I was a child, a lot of family friends were poets. They were friends of my parents and then they became my friends when I grew up. One of Ukraine’s most prominent poets who was just last week covered in the New York Times, Ihor Kalynets, was one of the first readers of my poetry, for instance. It was having support like that, having people who I could show work to and who were generally respected – at least by me, maybe they were not adequately valued by the state or by institutions -, that I could rely on feedback and who would say that it makes sense for me to continue to work on poetry, even though I would never earn a living or get any great fame or glory this way.

My father, who had dedicated his life to interpreting the poetry of others, spent most of his career being unrecognized, I think until he was about 60 actually. Then he got a lot of recognition because Ukraine became independent and he was showered with prizes and awards. But I think our way of living as I was growing up accustomed me to the fact that, if you want to create art and you want to do it with integrity and stay true to your calling you have to be ready to sacrifice certain things. And I think that’s part of the reason why I permit myself to focus on poetry. If you’re interested in a larger audience and commercial success, it’s much better to focus on writing novels or creating the type of writing many people are willing to read, which I think would be beautiful and very satisfying, as well.

I: Do you write mainly in English or also in Ukrainian?

O: I’m close to 40 now and I’ve started writing in English at 35. Before that, I only wrote in Ukrainian, even though I’ve lived in the States on and off since I was 15, so I am bilingual. I would do most of my academic writing in English, I teach in English. But it was never a language of poetry for me.

As I mentioned, I have a ten-year-old son and we were living in the States at the time that the war broke out in 2014. A couple of years later, he went to elementary school and we discovered that he couldn’t really speak English. We were speaking Ukrainian to him at home and we assumed that whatever pre-school education he was getting, was giving him enough exposure, but it turned out that in his pre-school he was mostly self-isolating and he was playing by himself. He wasn’t engaging with other children because they couldn’t understand him. So, to help him with his language skills, I switched to English with him, so that he could be a part of his elementary school community and make himself understood and not feel so frustrated and embarrassed. I think part of it was that when he would say things and not be understood, he would just shut down.

I think speaking English with a person who I have this very intimate, close relationship with, using it as a language of love with another person, has really changed my relationship with the language itself.

I actually started thinking of lines in English, something that never happened to me before. The way I write poetry is that a line, a verse, or a stanza comes to me that I use as a basis for growing a poem. Before, it was always in Ukrainian. I think it’s having this very emotional, familial relationship with the language that made it a language of poetry for me.

I: You also translate poetry. What is something about Ukrainian writing that stands out to you when translating? Are the topics you choose not to write about generally not represented in Ukrainian poetry?

O: There are other people writing about this, and interestingly, when we started looking at the poets writing about war, there were two poets who had written war poetry predating the Ukrainian war and we included those poems. Those poems were about the Yugoslavian wars, the wars in Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia in the 90s, and the poets have close ties to those communities – Kateryna Kalytko has ties to Sarajevo and, I think, Ostap Slyvynsky also knows people who have lived through those wars. I have close college friends who have also survived the war in Bosnia. And they were already thinking about these themes from the perspective of survivors because they have observed the war, people who were close to them, and those outside of their own community. I do think that Ukrainian poetry has become very different in the past eight years and I think part of it is a change in intensity – the intensity of emotion that the poetry has been forced to reflect. Another aspect of it is the demand for the formal innovation that’s required by the changing world. So somehow the old language and the old ways of creating art were deemed to fall short, they were inadequate for creating meaning out of what the poets had witnessed and were continuing to bear witness to.

There are different language phenomena that the poems capture which have to do with trauma and also with distancing in conveying those experiences. One of the strategies that we have noticed was an adoption of infantile language, like babbling where the voice of the poem is reduced to a childlike condition of having to come up with meaning in a confusing world, of making sense of a buzzing and blooming and roaring and wailing sensation. When you’re a child, you have to make sense of the world anew, it’s very fresh and strange. The poets who adopt this strategy often write like they’re learning to speak again in this changed world. Another strategy is docu-poetry, where the poet is viewing and describing events or people as if from a third-person perspective. There are very few qualifiers there, very few adjectives or adverbs that would guide you towards how you are supposed to feel about what is being said. Just mostly stories or images, often harrowing, dumbfounding, that leave it up to you to react, to make sense of what’s happened there. Then, there are also aphasic phenomena, poets showing what it’s like to forget words or to mix them up. Something we’ve just discussed when we talked about refugees is how language gets disrupted by the traumatic experience. Aphasia is a condition where you have trouble picking the right word or just forget the word or use one word instead of another. These substitutions are very telling about how memory and displacement work for things we don’t want to remember or are failing to make sense of.

One of the very interesting phenomena is wonderfully exemplified by the poet whose book we just published as a self-standing volume, it’s called Apricots of Donbas by Lyuba Yakimchuk, she just came to Vienna yesterday with her son from Kyiv. Her poetic strategy is deconstruction. She breaks words apart, especially names of places and people that have been destroyed by the war, to thematize, on the level of the language, what it does to our world and to the things in it. This strategy is especially interesting because it marks a relationship of continuity with the Ukrainian futurist movement of the 1920s. The Ukrainian Futurists talked about destruction or deconstruction as the necessary stage that art has to undergo before we can build new art for the new world which would be fair and just and beautiful. Yakimchuk uses this deconstruction of words and images to show the disappearance of meaning, where it’s not going to be replaced by anything better or more just, it’s revealed as bare naked factura, perhaps no longer good for anything. We address this point in our introduction to her book: how war tends to transform things into garbage, homes into rubble, how it wastes away people, animals, landscapes.

I: Regarding these intricacies of structure and meaning, what are some of the most difficult aspects for you of translating Ukrainian poetry into English?

O: A poem is a self-sufficient unique thing that exists in a particular context – a singularity – and that is what makes translation so difficult. You have to reinvent the thing in a new language with new sounds, new words, and in a different context, moreover keeping in mind how people in that culture view the world, perceive value, how they understand themselves.

So, poetry translation is an impossible task because it’s not words that you’re translating, but you are basically transplanting an experience, a mood, a transformation of whatever the poem is supposed to do, the event it commences, constitutes.

To accomplish that, often you have to change things around. You cannot just take the propositional content and translate it in a way that Google translate maybe would as if it were an ordinary conversation because it’s not ordinary speech that you are trying to transcribe – you are taking a bit of magic and you are trying to get that magic to happen again for a new audience in a new context in another language. I think of poetic translating as twinning – creating a twin, rather than creating a copy. So, the best translations of poetry, in my opinion, are usually translations by poets. Of course, there can be really excellent non-poetic translations of poetry that serve a different purpose. They are tasked not with creating magic, but with telling you what the words on the page mean. An excellent literary translator can show you this magic with their words even if you’re not poetically minded. Whereas somebody who is just translating the content can prepare you for the experience or give you a glimpse of what it could be like to have the experience. They could guide you right up to it – but the work would be on you – it’s up to you to experience it on your own somehow.

Read part two of this interview here.

To read more of Oksana’s work and stay updated on upcoming projects, find her website linked here.

For more information and a deeper insight into Words for War, check the recent BBC audio essay series on the book here.

Reviewed by Sarah Guvi. Proofread by Anita Ghoreshi.

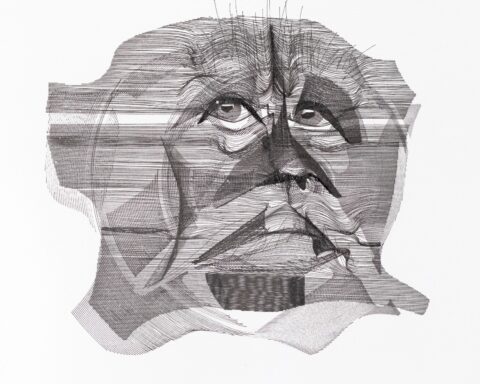

Header image by Natalya Mykhailychenko.