The Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games went ahead successfully this year, despite the looming threat of the Delta strain of Covid-19. It also went ahead without the support of the Japanese people, who were understandably concerned about the health risks posed by the coming and going of thousands of international athletes and their support staff. However with billions of dollars in sunk costs and the hopes and dreams of the world’s elite athletes on the line, the games took place, albeit with a 12-month delay.

After the experience of the last 18 months, it felt almost impossible that such an event could even take place. Transporting people from across the pandemic-ridden world to one location to compete together, sweat together, laugh, cry and likely share a celebratory drink or two didn’t seem like a wise idea. To combat these fears, the Olympic organisers put in place strict Covid-19 safety plans. Spectators were no longer able to attend in person and TV screens broadcast empty seats in eerie stadiums devoid of crowds cheering.

In spite of all the negative press and the anxiety and the uncertainty that permeates these times that we live in, the Games felt surprisingly joyous. For those still experiencing lockdowns and restrictions, passing expert judgement on synchronised diving was a welcome distraction. Cheering at the swimmers as they broke record after record while still in pyjamas at 3pm in the afternoon was a genuine highlight. The dedication, talent and pure grit displayed by the athletes in Tokyo seeped into our collective psyches.

And don’t despair, there is still more joy, heartbreak and edge-of-your-seat excitement to come. On August 24 the Paralympic Games began, which showcases more of the world’s best athletes competing at the pinnacle of disability sport.

Photo by Miguel Machado on Unsplash

A history of disability sport

Disability sport can be traced back to the 19th century when the first Sports Club for the Deaf was established in Berlin. Shortly after in 1914, the first International Silent Games took place in Paris bringing together hearing-impaired competitors from nine European countries. The Deaflympics, as the games would come to be known later, began important societal discussions about the welfare of deaf people at the time, who were often treated as outcasts and intellectually inferior. The event provided a valuable platform for deaf people to speak for themselves, as the games not only starred deaf athletes, but was also organised and promoted entirely by the deaf community. The Deaflympics take place every four years, with the next games scheduled for 2022 in Caxias do Sul, Brazil.

The origins of the Paralympics

While the Deaflympics paved the way for international disability sporting events, the origins of the Paralympics lie in World War 2. The neurosurgeon and spinal injury specialist, Ludwig Guttman, cared for many service men and women who had returned from the war with various kinds of paralysis. He believed that physical exercise and sport in particular helped his patients, even severely disabled ones, to live healthier and happier lives. Building on this belief, Guttman decided to organise a sports festival for retired service personnel to promote his approach to therapy and also showcase the abilities of those living with often debilitating injuries.

The Stoke Mandeville Games (named after the London hospital where the patients were treated) took place in London 1948, on the very same day as the London Olympic Opening Ceremony, with 16 service men and women taking part in an archery competition. This was a historic and symbolic moment in disability sport.

The Stoke Mandeville Games grew into an international event for spinal injury patients and by the 1950s had acquired the nickname of the ‘paralympics’. In the following years more and more of the athletes competing were no longer patients themselves but were outside of the hospital system and leading independent lives. In coming years the games became not only about individuals competing against each other, but rather national teams of athletes representing their countries. At the same time the games became a more organised and professional sporting movement, as funding and support for para-athletes increased and the event became more well known.

The Olympics and Paralympics combine

The marriage of the Olympics with the Paralympics was gradual. Days after the Rome Games in 1960, 400 athletes with disabilities gathered to compete in a number of sporting events. In 1976 the first Paralympic winter competition was held following the Winter Olympics in Sweden and included an opening and closing ceremony. Organisers of the Paralympics came up against many barriers to inclusion in the early years, like Olympic Village facilities that were not fit for purpose for people with disability (there were no lifts at the Rome games) and lack of funding.

Finally the International Olympic Committee and the International Paralympic Committee reached an agreement to host both events at the same time, with the first official Paralympics held alongside the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics.

Today the Paralympics and the Olympics take place together at both the Summer and Winter events. Countries bidding to host both events must demonstrate that they will provide a barrier-free experience for both Olympic and Paralympic competitors and promote both events as welcoming of diversity and inclusion.

Photo by yaron richman on Unsplash

The impact of the Paralympics

In 2021, the Paralympics will showcase the world’s very best disability athletes across 22 sporting events. However beyond the incredible talent and dedication of the individuals competing, the games have had an immense impact on perceptions of disability at many levels. For instance, when China was invited to send competitors to the 1960 Stoke Mandeville Games in Rome, the official statement was that disability simply did not exist there. By 1983, there was a Chinese Sports Association for Disabled Athletes established and a small national team was sent to the 1984 Paralympics in New York. Fast forward to Athens 2004 and the Chinese Paralympic team came first overall, demonstrating the significant shift in attitude that had occured over a few decades. In 2021, China sent 251 athletes to the Paralympic games to compete in 20 of the 22 sports.

But the success of the Paralympic movement lies not only in the increasing numbers of athletes competing at the games but also in fostering a spirit of inclusion. A new global campaign will launch at the Tokyo Paralympic Games to promote disability visibility, diversity and inclusion across the world. The campaign, entitled #WeThe15 brings together international organisations from across different industries like sport, the arts, business and policy makers to shine a light on the 15% of the world’s population that live with a disability. The campaign calls out the different ways that people with disability experience discrimination and ableism at all levels of society.

The Paralympic movement has successfully integrated disability sport into the mainstream arena, raising awareness of the physical, social and structural barriers that exist for people with disabilities. Despite this, there are some ongoing challenges to inclusion even within the movement, with some critics suggesting that there are inequalities between athletes with a physical disability and those with intellectual disabilities. While athletes with intellectual disabilities competed in the Sydney 2000 games, they were removed from the schedule for a number of years to return again in London 2012. It appears there is still a way to go.

The Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

These games will be another much needed form of escapism this year for those stuck once again at home.

The calibre and dedication of all the Olympic and Paralympic athletes has been amazing to see in light of all the challenges faced and the most wonderful form of escapism for our times.

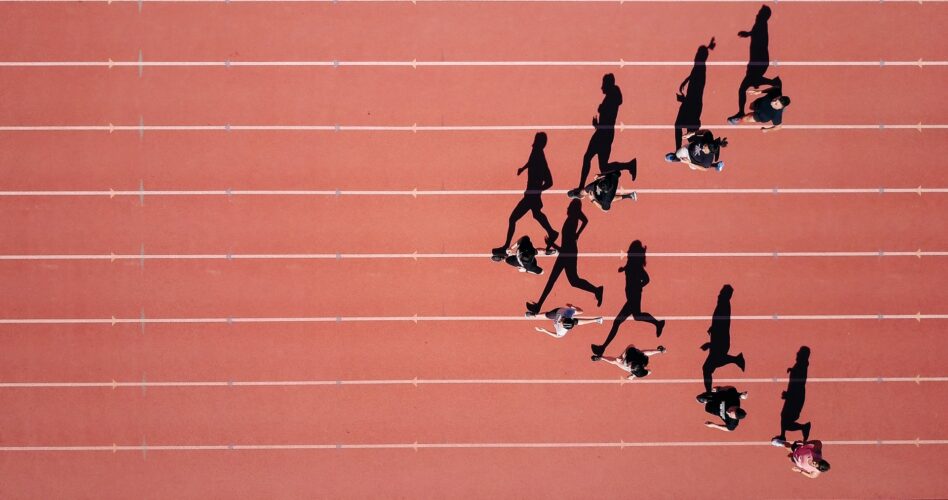

Cover photo by Steven Lelham on Unsplash