When we think of nurses, we imagine kind, selfless human beings who place compassion at the center of their universe. Indeed, being compassionate is practically part of the job description. However, many nurses and other healthcare workers often find themselves feeling numb and burnt out due to the immense pressure, pain and trauma they have to face every day.

Christie Watson is the author of the international bestseller “The Language of Kindness” and a Professor of Medical Humanities. As a former nurse who has experienced compassion fatigue, Christie wants to make people aware of the sacrifices nurses make for us, and what we can learn from them.

I had the pleasure to interview Christie after her TEDxVienna talk in 2021, to talk about the origins and consequences of compassion fatigue, and how nursing uncovers some of the issues still prevalent in our society.

When did you start feeling compassion fatigue? Did you notice a change right away?

So, most of my career as a nurse – and I’m not a nurse anymore – I worked in intensive care, and particularly children’s intensive care. I think, probably when I was a junior staff nurse, I didn’t have any sense of burnout. It was something that gradually crept up on me over the years, and by the time I was a senior sister I really felt it. It was sort of the accumulation of working with tragedy, but also systemic and organizational issues around poor staffing or things like low morale. I think these sorts of systemic problems around not having enough time to be able to deliver the care that you want to deliver but also that patients deserve, are the most challenging. It was never the job, never the patients, never my colleagues. I think the thing that sort of caused the creeping up of compassion fatigue was the politics.

And how did this affect your work? Did it become worse over time?

Yeah, I think – probably. I mean I was functioning. I just remember having some really, really sad days. And a bad day at the office when you’re working in children’s intensive care is a bad day at the office. I remember having some really brutal, awful experiences in going home and not crying, and I remember thinking – that’s a really odd lack of emotion. And a sign of depression, if anything. I was acutely aware of that, and just thinking, maybe I feel a bit numb. That was the word that kept coming to me. So, I was performing at my job as I always was, it was more of a sort of internalized lack of feeling or numbness that I was experiencing. This kind of clouded over into my days or my time off – I just didn’t feel any joy. It was like depression, that’s how some people would call it.

So it also affected your private life?

Yeah, work was so busy and it’s not that I was not enjoying my work. I still enjoyed it and got a sense of satisfaction from it, but I just didn’t really feel things that I should’ve felt. And I wasn’t sleeping properly, and all these other things that go with compassion fatigue. It did creep up on me, but it never got so severe that I wasn’t able to work because I know some colleagues who had to go on stress leave and things like that. So, I was lucky in that sense, but it was quite a strange sort of low mood and a bit of apathy. And that’s when I knew that it felt dangerous for my work because not crying is such a red flag that something’s wrong.

Some of my friends work as nurses in the UK, and they often tell me how hard the job can be, both physically and mentally. Nurses give so much of themselves and as you said “place compassion at the center of their universe”- in your opinion, how is it possible not to lose oneself amidst all these emotions?

I think people working on the front line right now are emotionally traumatized. And if they weren’t then it wouldn’t be right because it’s such an extreme experience, such an extreme time that we are all living in. This is true even for people not working in hospitals, but particularly for people working in hospitals and care settings. I read some research that talked about how the number of nurses in intensive care with PTSD or PTSD symptoms is just escalating. The mental health of clinicians is a massive worry right now because the workforce is flimsy at best. We don’t have enough nurses, and people are leaving in huge, huge numbers because they just can’t cope with the demands of the job and the situation that we are in. I am not surprised that your friends are struggling. Even if there are ways to help in terms of wellness and self-care, the problem is actually much bigger than that. The problem is systemic, organizational and political. I really think that the absolute priority is to pay nurses appropriately for the job that they’re doing, to make sure that they are getting their annual leave and their time off. Make sure that they have things like regular breaks. You know, these things sound so simple, but if you haven’t had a break for 8 hours and you are dealing with a really difficult situation, the next day you might not feel like going to work. It’s about managers, line managers, mentors – but effectively the government, really thinking about and prioritizing the mental health of nurses to protect them. And if they protect the nurses, then you protect the patients – and that’s the whole idea.

What do you think of the image of nurses in society, given the current situation? And is there anything you would like to change about it?

There is a very damaging narrative about nurses being heroes and I think it’s incredibly unhelpful. You can see people’s well-intentions about calling nurses heroes, they are just showing their love for them – but actually what that does is it weaponizes the government to be able to create martyrs. So, heroes do it for the love of the job, not for the money. You don’t need to pay them properly and you don’t need to give them appropriate PPE if they are dying in large numbers, because they are heroes. They are out there on the front line. The war-time language rhetoric that we are hearing, and the idea that nurses are heroes is really, deeply unhelpful.

I keep coming back to that phrase that nurses are “safety critical rigorously trained professionals” – and that’s the bit nurses and the nursing profession wish the public would see them as. I am not quite sure if it’s there yet. I think there’s an enormous amount of respect and thanks to the nursing and medical profession, to anyone who’s working in those sorts of roles at the moment. But I do think that the public in the UK particularly don’t have an understanding of the academic rigor of the discipline, and that it’s a profession. They almost still see the sort of angels, heroes narrative. And that, particularly over the pandemic, has been deeply problematic in terms of keeping nurses safe and making sure they are paid appropriately for the qualifications, but also for the job that they’re doing.

Do you think this has something to do with nursing being an overly female profession?

Absolutely. 89% of nurses in the UK are women. In nursing here – and I can’t talk about the rest of the world, but the vast majority of management roles are men, even now. There is a huge pay gap – even in nursing where it’s 89% female! So, it’s massively gendered. I do think that “care” has become a dirty word, I think that it’s seen as “less than” because it’s seen as “women’s work”. And so it is definitely gendered, and you know, medicine’s come a long way: most doctors are now female actually. But the nursing profession hasn’t attracted men, because it doesn’t yet value the women in it. The way to attract men into nursing – which is what we all want – is to value the women that are already in it and make the whole of the profession much more equal and better.

You also talked about how people were more compassionate towards each other at the beginning of the pandemic. Why do you think people lost their compassion and what made them, as you said, “close their curtains again”?

Yeah, this is a very interesting question I’ve been thinking a lot about. It was wildly different in the beginning: people’s attitudes, enthusiasm, and energy I guess, for delivering compassion to others. It seemed like a big moment, in terms of our values in society, and it felt like a sort of change towards the right things. Despite the horrors and the tragedies of the pandemic I did feel quite buoyant and excited about the prospect that we would come back as a kinder, more inclusive society, because I could see these changes all around me. And then literally over night something turned again, and I can only assume it’s back to that compassion fatigue.

In a way, it’s quite hard work to be hopeful constantly. I think that the uncertainty of this time has been probably the biggest challenge in terms of people’s energy for compassion. We’ve all had those moments about four or five times throughout the last two years when we thought that this pandemic will soon be over, and life is going to come back. To realize this sinking feeling again, when there is a new variant, when something terrible happens in our personal life, or the idea that we are coming to terms with the fact that life will always be different. There is an awful term here called the “new normal”, I don’t really like it as a term, but we are in a different world now, and we won’t be going back. There will be going forward in a different way and that’s quite a big change to come to terms with, collectively and individually.

Compassion, we realized, is how history will judge us. And it’s how history should judge us.

Christie Watson

I do think that it’s the uncertainty that makes people change from the buoyancy and the hope to turning inwards, because that flipping from all great or it’s all terrible has left people tired, fatigued and a bit numb. They are fearful of feeling hope, because every time we have felt hope, something disastrous has happened. When you become afraid of hope, that’s a really dangerous path to apathy and a way of shutting down. And it does feel like we have sort of collectively shut down – but quickly, after that first period. How soon we forget is something that I keep coming back to as well, because you know, I think that it is astonishing how quickly we’ve forgotten what it was like in the beginning of this, what it was like before. Human nature is such that we are adaptable to even the most extreme circumstances, and we forgot really quickly how we’ve felt before. So, I think it is really important to document and record and have something scribed, like what you are doing right now. When we are old, when you’re a great grandma you can look back and say: “Oh I remember that interview with Christie, I remember thinking about this!”. The reason people are feeling compassion fatigue is because they are scared of hope.

In this age of isolationism and division and hatred, it is not feeling anything that we all must fear.

Christie Watson

Watch Christie’s TEDxVienna 2021 talk here:

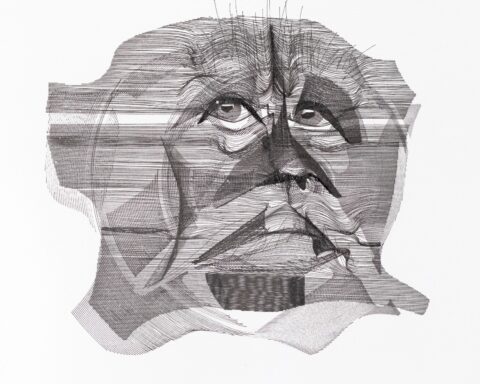

Header image by Christina Selwicka