Ron Haviv is an American photojournalist who primarily covers conflicts. Besides documenting war crimes and conflicts, Ron’s main aim is to raise awareness about human rights issues all over the world.

Throughout his nearly 30 year career, Ron has documented over 25 conflicts in over a hundred countries. An impressive number, not only in terms of Haviv’s work but also the amount of violence in our world.

To help spread his ideas, Ron Haviv co-founded the VII Foundation which “seeks to challenge complex social, economic, environmental and human rights issues through documentary non-fiction storytelling and education”.

During his talk at TEDxVienna 2021 UNTOLD, Ron described his experiences as a war photojournalist and spoke about the role of photos in shaping history, and the injustice in the world.

In our interview, an Emmy nominated and award-winning photojournalist Ron Haviv talks about responsibility, impact, problems, challenges, power, and possibilities of photojournalism and journalism in general.

How did you start doing photography? What made you passionate about it back then, and what has changed in the last 30 years, when you reflect on it?

The start wasn’t very romantic, as I had no real interest in being a photographer when I was younger. In the United States, when you go to university, you have to decide pretty quickly on what you want to do for a career. All I knew was that I wanted a career that would not involve me being in an office under bad lighting conditions, but one of the jobs that would allow me to travel. So I thought about journalism. I studied to be a writer for a few years.

“My constant goal is always to try to have an impact with my work.”

And one of the jobs I had at that time to make money, to help pay for university, was working for a fashion photographer. This is where I started to get exposed to photography.

At some point, I decided that rather than being a writer, I would be a photographer. For some reason, instead of choosing to be a fashion photographer, I wanted to become a photojournalist. I taught myself photography, took a basic introduction class, and graduated. And entered this world of photojournalism.

Immediately, I was the youngest photographer working in New York. I entered a world where people were incredibly helpful to the next generation. They wanted to make sure that people working were dedicated to telling stories that needed to be told. People gave me advice and helped me do that.

There is a reference in the talk today – I met a photographer named Chris Morris who gave me a plane ticket, and we went to Panama together. We spent some time together in other countries documenting different conflicts, and I learned a lot from him. He was my first real mentor overseas.

Based on the experience I had with the photographs from Panama and Bosnia, I started to understand both the power and the limitations of journalism. During that period of time in the world, from 1989 and the next years, the world has changed dramatically, and I was able to document much of it: I was in Berlin when the Wall fell, in Kuwait city when it was liberated after the First Gulf War, I photographed Nelson Mandela coming out of prison.

It was very inspiring to be documenting these historical moments in humanity. My constant goal is always to try to have an impact with my work. But it doesn’t always work. In fact, most of the time, it fails.

During my career, in 30 years, I’ve documented three genocides: Rwanda, Bosnia, and Darfur. The hope always was that after World War II, after Cambodia, and so on, genocides would no longer exist. So, we, myself, and my colleagues try to stop the next one from happening and teach lessons through our work. But it’s a difficult lesson for people to learn. And it’s also why it is incredibly important that we create these bodies of evidence to hold people accountable for both their actions and their inactions.

“The idea of amplifying voices to make voices that are not heard louder to shine”

Technology and the way we work as photographers have changed over the decades. We have digital photography now. Technology and tools change, but the motivation, the idea of amplifying voices to make voices that are not heard louder to shine, stays. They are clichés to some degree, but they also still remain true. Photography can still have an impact. For example, the photograph of Alan Kurdi, the Kurdish boy on the beach. This photo has influenced the change in the German foreign policy about migrants.

Photography continues and will always continue to have power, even though more and more people take photographs. The supply grows bigger, but the audience will grow more appreciative, and the impact can be very powerful.

In your talk, you mentioned that you felt that you failed as a photojournalist for some time. Where do you find the strength and motivation to not give up on your work?

There are times when I feel that the work has failed to have any kind of impact. This is certainly in the short term, but I learned early in my career that photographs have other lives, and we don’t always know how they impact people. It allows me to still have the encouragement that the photographs do something. I don’t think that there are careers in the world where people affect the lives of strangers in this dramatic way as journalism. That continues to be a motivating factor.

Another motivating thing is that, as I’ve grown and grown older, I have understood there’s a need for the next generation to be taught this type of work. Teaching young photographers is important but also incredibly inspiring on the selfish level.

My colleagues and I started The VII Foundation as an educational branch called the VII Academy. Our mission is to teach visual journalism free of charge to photographers from non-G-20 countries. We started this about two years ago, and so far, we’ve taught more than 700 students from around the world. And continue to do that.

“Photography continues and will always continue to have power, even though more and more people take photographs.”

I think that we are able to contribute to the next generation to take over from the work that we’ve been doing. That also continues to give me hope that there are people that will continue to tell these stories, to have an impact, to make things a little bit better.

From your talk, we’ve learned that photography has huge power. But where do you personally get the power and strength to pull the trigger? Were there moments when you weren’t emotionally capable of taking a photograph?

It is important to acknowledge that anytime I’m going to cover a conflict, from the time the plane leaves my home to the time I get back, I am scared. And fear, I think, is a very important factor when documenting these types of situations. If you’re not scared, there is probably something wrong with that person. The question is how you use fear.

And when you use fear, you should try not to make any foolish mistakes. I’m not the one who believes it’s worth dying for a photograph. I want to make sure I’m alive the next day to work. But again, of course, you take chances in dangerous situations, but I try to mitigate the risks.

I suffer from post-traumatic stress. At the beginning of my career, it was not really understood and not talked about. There was rather more a cliché of the journalist drinking at the bar alone. But today, with the work of doctors like Dr Anthony Feinstein, who has done great research on stress and journalism, it is much more accepted. It is out of the closet. There are experts who help us deal with what we experience and be able to recover from that. It is an important factor.

The idea of kind of being overwhelmed with the job is true. There are times when people quit this job. This is not something that many people do for as long as I’ve been doing it. Everybody is affected by the work differently.

In terms of being emotionally incapable of taking a photograph – that does not apply to me very specifically. I feel a true responsibility of being the eyes of the audience, and then it’s not up to me to censor something. So I try to photograph with respect for dignity and permission, but with that in mind, I am not self-censoring. I try to document whatever I see.

Talking about mental health. Do you ever get cynical while doing photos because of all the violence you see? Are there times when you do not feel compassionate about what you see? For example, like doctors who cannot be compassionate towards each patient since it is almost impossible to process these kinds of emotions daily.

I do not at the moment, and I have set myself that if this type of work starts feeling like a nine to five job where I automatically take photographs without really feeling anything, then it is time to do something else.

It’s not the same as a doctor, though. Because a doctor still achieves something, regardless of how he or she feels. But for the photography, there needs to be an emotional connection to the subject to some degree in order for that to come across in the image, for the image to be successful. If you remove that, then the photos are not as good, and somebody else should probably be doing that work.

So there should still be an emotional connection and some emotions present in work, but you have to control them in order to pull the trigger at the right moment?

Exactly! It is about finding a balance.

There’s no point in me going somewhere if I am overly stressed or upset, and I can’t take a photograph. Then why am I there?

You have to find the balance between being able to have an emotional connection to what you’re seeing for it to come across in the photograph so that the audience has an emotional connection to your image as well. And if you’re able to find that balance, then you are able to work.

How do you process what you see?

I think that I was extremely fortunate that those two photographs happened so early in my career that I was able to see that even the lack of reaction is a reaction. From that, I knew that my photographs were having some sort of impact. So I rationalized the reason for me doing this.

I think if I were just setting my photographs off into the digital sphere and not exactly understanding what was happening, it would be much more difficult for me to rationalize going to these places. There were, without questions, some limitations, but there was also the power of photography.

It continues to be a motivating factor and continues to rationalize why I do it. This helps me then process some very difficult things with the understanding that I have suffered from PTSD, but at the same time, I still think I’m capable of doing this work. It is so important for me to do it.

You have the VII Academy and the Foundation, where you teach photography to the next generation. Do you see a lot of difference in how the younger generation processes things in terms of taking photos? Do you think the younger generation puts other values into the photos?

“The most important thing is the way the photographer sees the world and what he or she is trying to say.”

Obviously, technology and the tools that we use have certainly changed since the beginning of my career till today. But that being said, the most important thing is the way the photographer sees the world and what he or she is trying to say.

Some of the newer conversations that are happening are about the subjects, about informing, and consent. It’s about expectations, the rights of the people you’re photographing, which is very essential to happen.

There’s also a conversation about who the photographers are themselves. What nationality are they? What race are they? What gender are they? What do they think about this or that? And are they the right person to be photographing this story? This is a live conversation going on in the world of journalism.

I think there are so many benefits from these conversations that photojournalism, in terms of the media, has often been a misalignment, especially when it comes to gender. That’s changing, but not changing fast enough. There are still other misalignments. For example, in America, there are not enough African American photographers. At the same time, there are not enough Iraqi or Libyan photographers, and so on.

And one of the things that has changed because of technology is that these photographers, whether they photograph with a phone or an affordable digital camera, are now able to tell stories of their own communities. This is a very big difference. The photographers can turn the camera onto themselves and their communities to document what’s going on.

“People can draw their own conclusions as an audience.”

Yet, at the same time, I’m of the belief that there’s still room for the older white male photographer who’s in some circles considered the active assistance of the photography now. There’s still room for me to be able to go in as a journalist and tell a story as well. My story doesn’t invalidate the story of the Iraqi photographer, and his or her story doesn’t invalidate mine.

It is amazing that the audience has now this ability to look at the story, like Afghanistan, and see it through the eyes of the Afghan photographer, an American photographer, an Asian photographer, and so on. And then they can draw their own conclusions as the audience.

I think it will be a lot of traumatic overlap where everybody’s photographing the same thing in slightly similar ways. So they’re going to be things that you learn more from the Afghan photographer because they understand the culture in different ways, for example.

But there is a movement now in journalism to eliminate: “the photographer that doesn’t have the right to photograph X”. This is a real conversation, and I think it cannot be a very beneficial conversation. It could also be a very dangerous one. We, as a community, have to find a way to make it work for everybody.

There are things that need to be understood, but at the same time, everybody has a viewpoint, and everybody’s viewpoint is valid, regardless of where they’re coming from.

This conversation is, for sure, important, but do you think that a journalist should choose or reject work? Saying, for example, that it would be better if an African American would take photos of this event? Or should journalists always be on duty without rejecting a job?

It depends on your agreement, but of course, everybody has a right to say no. Yet, I don’t think that’s correct because I think that everybody’s different perspectives bring value. I don’t think it’s fair to say because I’m not an African American, I shouldn’t be able to photograph an African American story. I think that there should be different views.

And I also think, especially in the world of photojournalism, if you would put the photographs on the table and tell me: this was taken by a man or a woman, by an African American, or white, or an Asian person, I wouldn’t always be able to tell you the difference. It’s not where the differences come out, but it is important for us, as a community of photojournalism, to really understand when we are going and not to say that no one has a right to tell a story.

It means that everybody should be able to participate. When I started my career, there were no Iraqi photographers contributing to the world’s understanding of Iraq. But now there are. And they are amazing, fantastic. It is also beneficial for the audience to have that.

Photography gives room for interpretations, and framing is a huge problem. Have you ever had a situation where your photos were framed in the wrong way and interpreted not in the way you meant?

A very good example of this is when a very well-known blogger from Russia used my Bosnia photograph a few years ago. It was during the war with Ukraine. He took my photograph from Bosnia and simply changed the captions. He said that the perpetrators were Ukrainians, and the victims were Russians. I put out a statement, but I don’t have millions of Russian followers.

So now there are millions of Russians who look at that photograph thinking it was a war crime against Russians. This is an example of how dangerous things can be. You don’t even have to manipulate the photograph. All he did was change the caption.

As a worldwide audience, we have to be very diligent in consuming imagery and understanding captions connected to photographs and the sources of work. We try to rely on trusted sources with integrity, but it’s becoming more and more difficult, and it’s becoming more and more dangerous.

So this is about media and digital literacy?

Exactly, which is a whole other conversation, but it’s incredibly important.

“We have to be very diligent in consuming imagery.”

You were in Washington DC and witnessed the Capitol riots on January 6th and took some viral photos. How was it being there?

It was pretty hot there. And incredibly disappointing too. It was really unexpected, given that America thinks of itself as being above everybody else. But I had photographed similar situations in Moscow and other places, so why shouldn’t it happen in Washington DC?

It is often said we still have to love all people, despite different views. People have to find the strength to educate others instead of hating because we are all human beings. Do you think that your photos can educate people?

I think it’s difficult, but it has to be done. It will take time. And in combination with many other things. A photo cannot certainly do it on its own. But, hopefully, with other conversations and other pieces of evidence, it will contribute to a more true understanding of what occurred and what’s occurring in the United States.

One last question. You have certainly seen a lot of horrible things while doing your work as a photojournalist. But was there a moment in your career that you remember with a smile on your face?

I have been a witness to a variety of different human activities: from heroism to mothers and their children doing anything they could to survive, still trying to help other people. There have been a number of different situations, and witnessing some of those things gives me hope for humanity overall. Because there are still people who will rise above differences to do the right thing.

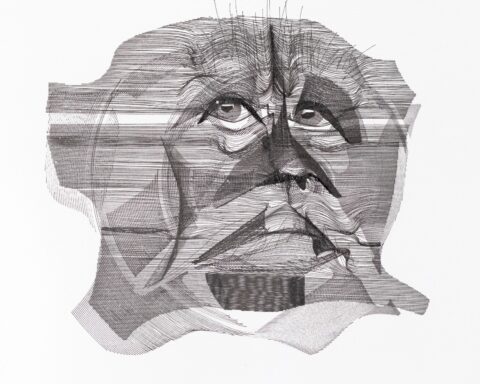

Cover Image: © Gavin Gough