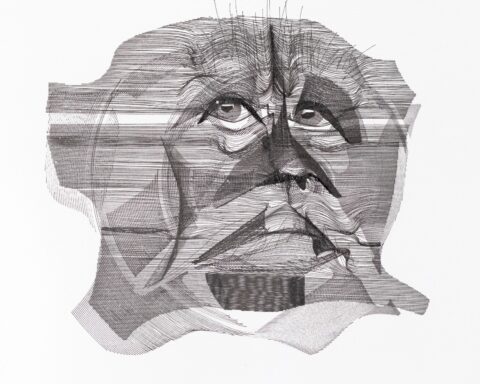

Founder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Urban Metabolism Group and Director of the University’s Environmental Solutions Initiative (ESI), Professor John Fernández has spent more than twenty-five years looking for innovative solutions to pressing sustainability issues.

Both an esteemed academic and a practicing architect, John possesses a deep understanding of the intricate relationship between urban design, technology, and environmental consciousness. A true pioneer in his field, he recognizes sustainability not as a mere concept, but as a practical matter, actively pursuing projects that bridge the gap between theory and real-world implementation.

As an entrepreneur, author, and member of more than fifteen organizations, groups, or task forces, John’s mindset is based on the understanding that the future of sustainability lies at the intersection of new technologies and social equity.

After his talk at this year’s MIT Europe Conference, we had a chance to sit down with John and dive deeper into his work, as well as all things sustainability.

“There is no moving forward in urban sustainability, or really any kind of sustainability, without an equitable approach.”

Prof. John Fernández

You’re currently leading the Environmental Solutions Initiative, and you’ve also founded the Urban Metabolism Group at MIT. As someone who has made tremendous strides in the field, has the focus of your work shifted at all since you began, especially given the pressing climate change? What are your priorities right now?

As an architect, I started working at MIT in green buildings, which was work that was needed in the United States at the time. The US was behind Europe in this aspect, it was not easy to build an energy-efficient building. Then we did the research, as many others did, caught up, and got to the point where it’s now possible to design a passive house, an energy-efficient house.

The following step for me was shifting to cities. I had to ask myself – how are cities unsustainable, and what can we do about it? That’s how the Urban Metabolism Group was founded. What we do is account for the resources required to run urban economies – materials, food, energy. That analysis has helped us to better understand what the pathways toward sustainability can be for different types of cities.

The approach is different when you make different types of buildings more sustainable – it’s the same with cities. A tropical city in a developing country is a very different scenario than a city in Northern Europe, for example. How you reach sustainability in either one of those is very different. This work then led to getting involved in a very wide range of environmental topics with the Environmental Solutions Initiative. I’ve committed to working across a vast range of environmental issues, but I must say that my focus now is reducing biodiversity loss.

Your startup, Lamar.AI, is also focused on making cities more sustainable. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

I’ve had the luck of having three great collaborators for Lamar.AI. Together, we noted that the most economical way to make a building energy-efficient is beginning with the exterior wall and making sure that it’s performing in the way that it was designed. And so we developed a company where we use drones and thermal imaging to capture the wall and see where there are leaks of heat and air. However, that’s something that can also be identified manually. The core technology is a machine learning model that would, through thousands of images, be able to identify thermal anomalies, and then to classify them. So you can fly a drone around a big building in a day, get thousands of images, and then within less than a second, you have all of those images processed so that you know where you should be repairing the wall. We’ve already done this for a couple of buildings at MIT as well, and they found it to be very useful information because it’s increasing the efficiency pretty dramatically.

AI is a bit of a buzzword right now, and it has become the topic of many debates. Do you think there are other ways in which it could be used, specifically when it comes to sustainable building?

AI is really central to the work we do because doing everything manually on a very large scale, surveying many buildings, would not be efficient at all in terms of time and resources. I think the application of AI to the environment is endless. Of course, there’s an emerging set of darker issues when it comes to AI – no question about that, but one thing that excites me a lot, and makes me very optimistic, is that the younger generation of engineers is immersing themselves in AI, and embedding that intelligence into the machines they’re creating. When it comes, for example, to the younger generation at MIT, one of the things that I’ve learned in the last few years is that they’re much more interested in using AI to address a problem in climate change or in biodiversity than they are to use it to make selecting a movie on Netflix more efficient. There’s a genuine interest to apply it to the real challenges we have, and I think we haven’t even begun to see the kinds of advances that AI will bring to many of the challenges we’re facing.

In spite of us still living in a world of trade-offs, MIT is focused on making advances and bringing real solutions to real problems. So much of what you do has a real-life impact. Do you think there are ways to take that and expand it, to replicate it, not only throughout the United States but across the world?

We’re actively engaged in doing that. I can give you an example: we are working on a project in Colombia in a town called Mocoa, that has suffered several large-scale landslides which have killed hundreds of people over the last twenty years. With climate change and increased rainfall, the risk of landslides is also increasing. There’s a lot of uncertainty about where people should build or live in this town.

So we started a project where we fly a drone, collect data on the landscape, and build a machine learning model that takes historical data and all the factors that lead to a landslide, and tells you with much, much higher probability where the next landslide is going to happen. As a planning model for the city, that is extremely helpful. What we want to do now is to develop a toolkit that’s powered by AI for climate threats, for towns and cities of various sizes. We’re about to expand into other parts of Latin America, into Brazil, and I’m looking to Africa as well, to provide a toolkit for the probability of extreme heat events, the probability of extended drought, and to use machine learning and AI to power those kinds of tools.

MIT’s philosophy is from idea to impact. There’s so much progress being made in research and scientific development, but there’s still a gap in the application of that in the real world. Do you think there are other ways in which to bridge this gap between the prototype and functional solutions?

There is an ongoing discussion at MIT about making the connection to real-world issues even more direct. So we have, as you just said, many examples where groups are very engaged with real-world stakeholders, doing work that has a very quick turnover and short-term impact. The Climate Grand Challenges, for example, is an institute-wide project to fund research projects that aim to do that within five years, returning real solutions that can be deployed.

But your question is particularly interesting because it brings up the role of universities. In my opinion, the role of universities should shift towards the mission of creating a sustainable economy, in the same way, and with as much energy and ingenuity as MIT did in the creation of an industrial world. That was the grand project of the late 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, and of course, technical universities were very prolific. But now it’s a question of shifting towards this different mission. It’s about creating the economic and technological and cultural conditions for a real sustainable economy. At MIT, I see a growing number of professors at all points in their careers, but especially those at the beginning of their careers, who are really integrating this mission into the research that they do.

“It’s never too soon to have a student become acquainted with the messiness of the world, so they become less intimidated by it.“

Prof. John Fernández

State actors are also notoriously slow in adopting new things. Especially when it comes to making cities more efficient and sustainable, collaboration is needed. Do you think there are better ways in which the scientific community can become more involved in policy-making?

A number of my colleagues are very involved in advising and drafting new legislation. MIT was actually significantly involved in a huge bill that was passed by Congress, which basically doubled the amount of funding that the National Science Foundation receives. It’s an extraordinary achievement.

On the other end of the MIT community, one of the things that the ESI has been doing is employing an engineering approach. You build a prototype, you test that, it fails, you build another one that’s better. So we started a group called the Rapid Response Group, which is meant to involve students in real-world environmental issues. We do things short-term, in phases of three weeks or three months. It’s activities like writing up a set of talking points for a congressional office on hydrogen or advising a company in Texas about storing oil underground. The topics are very diverse. They’re all undergraduates, and the reason we’re doing this is to support them in learning by doing.

Being an engineer in a classroom or in a lab is one thing, but actually going out and getting involved means realizing that there are all these other factors to be considered. It’s never too soon to have a student become acquainted with the messiness of the world, so they become less intimidated by it. Whatever it is that they’re learning, they’re becoming acquainted with that along with their formal education. Besides the Rapid Response Group, there are a number of other programs at MIT that get undergraduate and graduate students more involved in the world beyond the campus.

We’ve all become more aware of the importance of both sustainable development and innovation over the last few years. As an architect, you’re no stranger to the concept of sustainable urbanization. What would mean, in your perspective, to create future-proof cities? What would they look like, how would they operate?

A central principle would be to eliminate fossil fuel combustion entirely within a city’s borders, as well as the decarbonization of the electric grid, on which cities are dependent. Phasing out oil and gas combustion to heat buildings, and using electricity instead would be a major change.

The second major principle is to leverage the services that natural systems bring to a city. The urban heat island effect refers to the fact that almost every city is higher in temperature than the surrounding region because you’re always metabolizing things within its perimeter. One of the most powerful ways to reduce that urban heat is to increase the amount of green in the city. Trees, tree canopy, parks. This also generates the possibility of greater biodiversity within the city.

The third principle is a circular urban economy – being able to recycle materials, water, food waste, energy. This is a really important strategy to have in place for cities, and I want to emphasize the fact that there is no moving forward in urban sustainability, or really any kind of sustainability, without an equitable approach. We can’t create a resource-efficient city that is deeply inhumane. So being very honest about how inequitable we currently are in the distribution of resources, even simple things like access to parks, is a principle of urban sustainability that will make the whole system more robust.

I’m originally from Romania, and coming from one of the bigger cities in the country, I can say that unsustainable urbanization is really becoming a problem. Do you think there are any cities in the world right now that are making progress and that we can look up to?

There are aspects of many cities that are very progressive and sustainable. Bogota, Colombia is a really interesting example of a very large-scale, very well-designed mass transit system, that was intended to make the city more accessible to much more of the population. A classic problem with cities is that, as they become successful, they create wealth. That wealth concentrates in the center, and people are driven to the edges. And so having mass transit that is not a burden to use is really important. They did two things very well: Firstly, they designed and built very good train and bus systems that extend very far and cover very large parts of the city. In addition to that, they saw the potential for really widespread bicycle use for commuting. The first time I went to Bogota, I was amazed by the thousands of people riding bikes every day. Because they built the infrastructure very intelligently and securely, with separated bike pathways, they have a wide range of people, from very young to quite old, who buy into the idea and actually do it.

Curitiba in Brazil is another example. Chicago for green buildings. New York City for its overall climate plan. Hamburg and Berlin for their heating and cooling districts. All very progressive and exciting. So the answer is that, thankfully, what’s happening is that cities are updating those systems that provide the best return in multiple ways, not just in CO2 emissions reductions, thus creating more equitable, livable communities.

Sadly, there are many examples of cities that are becoming really difficult places to be as well. The danger of extreme heat leading to mass casualty in various cities in India is higher than it’s ever been.

I’m 26. Many of my friends are currently working, in their specific areas of expertise, on projects that have to do with sustainability. Although it’s such an important topic, they’re all having trouble accessing resources on sustainability, on efficiency, whether that’s information or data, or experts to consult. Do you think there are ways in which we could make it easier for the upcoming generation to access both resources and mentorship on this topic?

The dissemination of important information is the responsibility of higher education. So, on the one hand, MIT has been a leader in the Open Courseware program, which makes most of the MIT curriculum freely available online. It was started by a past president of MIT, Charles Vest, and it was regarded as a pretty radical idea at the time, to say that we’re going to take all this material, and we’re just going to put it online and make it available to anyone. It’s been very successful, and I can say that there is a tremendous amount of information that is available there.

Another thing is that there are more and more people like me, who are now spending most of their time talking about sustainability, not just to corporate audiences, but to lots of different kinds of audiences. And again, this is where the mission of higher education should shift toward sustainability. In my opinion, the primary role of education now should lead to more accessibility. But it’s a work in progress.

Made possible by the Austrian Federal Economic Chamber in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the MIT Europe Conference took place between 29-30 March in Vienna. Local and international entrepreneurs, researchers, and technology experts had the unique opportunity to gain insights into the current research work of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The conference focused on innovative technologies in the areas of sustainability, energy, and nutrition, powered by the motto “A Changing World. How Technology Tackles Global Challenges”.

Interview proofread by Julia Zmölnig.