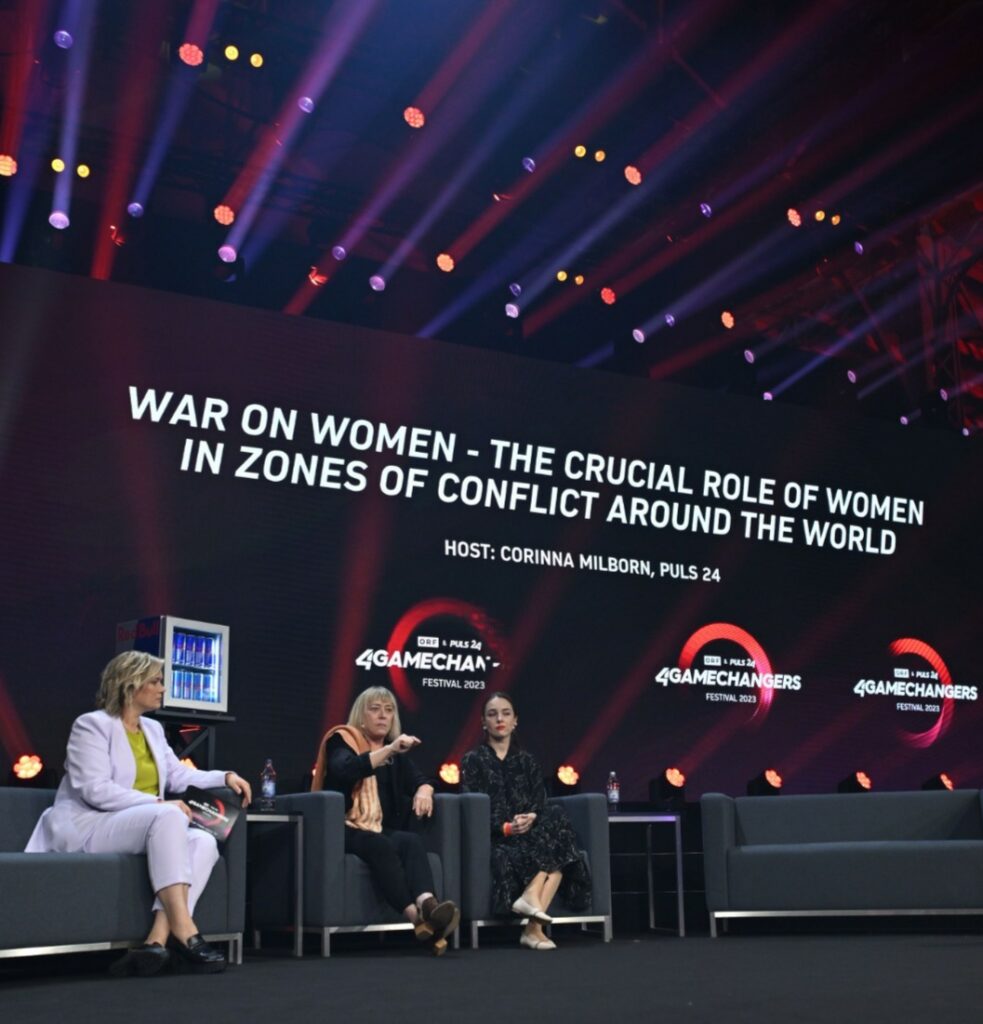

‘‘War on women’’- this was one of the headlining discussion panels of this year’s 4GAMECHANGERS Festival in Vienna. Focused on the voices of women, be they witnesses, victims, or advocates of war-torn areas, the panelists, among which was Jody Williams, brought attention to the vital role women play in the peace process.

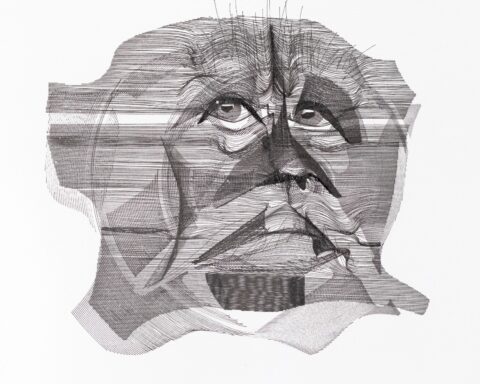

Jody Williams is an outspoken American political activist, serving as the founding coordinator of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) formally launched in 1992. The initiative brought about the signing of the international treaty banning antipersonnel landmines, now also known as the Ottawa Convention. In light of her work on ICBL, Jody was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, thus becoming the tenth woman – and third American woman –in its almost 100-year history to receive the Prize.

In her fight for women’s rights and justice, Jody and her colleague Laureate Dr. Shirin Ebadi of Iran took the lead in establishing the “Nobel Women’s Initiative,” together with sister Laureates Wangari Maathai (Kenya), Rigoberta Menchu Tum (Guatemala) and Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan Maguire (Northern Ireland). The Initiative makes use of the prestige of the female Laureates in order to echo the voices of women whose life stories inspire societal change, freedom, and equality.

Her work goes beyond public speaking and advocacy, Jody is also known for her active role in the war-torn areas of Central America, especially for projects on the wars in Nicaragua and El Salvador, where she “spent the 1980s performing life-threatening human rights work.”

As an experienced advocate of freedom and civil rights, Jody participated in panel discussions at this year’s 4GAMECHANGERS Festival in Vienna, where she sat alongside other female activists, such as Shirin Ebadi of Iran, Amal Clooney or Nadia Murad, shedding light on the importance of amplifying women’s voices in times and zones of war. After her discussion, I got to sit down with her and learn more about her work, life, and eagerness to fight for change.

You’re an advocate for peace and human rights. Has this passion come about organically or was there a specific event in your life that triggered this for you?

It was the ancient history of this world, but it was during the US military action in Vietnam. I was in university and lots of people I knew were being conscripted to fight in a war they knew nothing about. They would be killing people they knew nothing about. A new culture they knew nothing about. And I began part of the protest against the war and that just continued on to Central America, landmines, and then the Nobel Women’s Initiative and here I am. Years later, still trying to make a better place of this world.

You’re well known for having won the Nobel Peace Prize with your campaign on banning landmines. Why were the landmines the focus of your work at the time?

Well, it wasn’t my idea. I was recruited actually by two organizations. One was Medical International from Frankfurt, Germany. I knew them from my work in El Salvador and they were partnering with the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation in Washington, DC and they wanted somebody to create a campaign to ban anti-personnel landmines. The Vietnam vets, of course, knew the impact of landmines during the war in Vietnam. If I remember correctly, the majority of woundings and mutilation, and ammunition for US soldiers was from landmines. They were brutal weapons.

And then they asked if I would try to create a campaign and I was sick of Central America at that point. I had been working on it for eleven years, and you know the situation was changing and I needed something new where I would learn at the same time, that I was trying to bring people together to protest the use of landmines and I accepted and here we are. It was a wonderful experience. I am privileged to have been able to do that.

In another interview, I read how winning this prize did not have the anticipated effect of feeling more empowered in your career. You were battling certain moments of doubt. Could you elaborate more on that?

It was because, and I quote a Nobel friend of mine, he’s now deceased, Archbishop Desmond Tutu from South Africa, we were at a Nobel conference at a university in the US and one of the students said to him ‘‘How did the Nobel Prize change your life?’’ and he said ‘‘Before the Nobel I talked and talked and talked and nobody listened. After the Nobel Peace Prize everything I say is a pearl of wisdom. ‘’

And for me, the difficult thing was not talking but suddenly I was being asked to talk about things that I hadn’t worked on specifically, unlike the landmine campaign, where I knew everything about it. And they were asking for my pearls of wisdom on other issues, and it made me feel fake in some ways. Not that I couldn’t talk, I could talk about anything, really. Give me two facts about something and I can really say I really know what I’m talking about. But I knew that I was kind of making it up as I went along, and it was a difficult transition. I wasn’t the only one. Mairead Maguire who received the Peace Prize in 1976 for her work against the war in Northern Ireland. She cried for the first 5 years after receiving the Peace Prize for similar reasons because suddenly everybody is asking her stuff and she’s like ‘‘What?’’.

There’s definitely much more attention being projected as a result of that.

Yeah, but I adjusted, and I learned how to, I hate to say ‘use the prize’, but used the prize to benefit the work I was involved in or to shine a spotlight on the work of other women, you know, in conflict zones around the world.

”If people wanted to contribute to something: Think about what makes you burn with righteous indignation!”

Jody Williams

In your activism work, you shifted your focus to various projects: from banning anti-personnel landmines to preventing the development of killer robots and advocating for human rights in Central America. What were the driving forces behind each of these areas of interest in your work?

When I thought about doing the panel a little bit ago I suggested that if people wanted to contribute to something ‘‘Think about what makes you burn with righteous indignation!’’ which is different from anger. Righteous indignation is indignation because justice is not being applied. What makes you upset enough is that you would like to do something to change it and if this something hits me that hard then I want to do something. I don’t jump into everything. It really has to make me edged.

The panel focused entirely on women in zones of conflict. How, in your opinion, do women’s perspectives enrich this discussion? How do you see the need to amplify their voices in this regard?

Because women were always seen as victims and women started saying we are not victims, we are survivors. We have powerful things to say about how society needs to change after the war. And one time, a few years back, in the Nobel Women’s Initiative, we were in some area for a press conference and a young man stood up and asked ‘’What do women bring to the peace process?’’. Oh, I wanted to slap him. I looked at him and said ‘‘What do men bring to the peace process?’’ his jaw really dropped, and he stood there, and he said, ‘’Wow, nobody has ever asked me that’’. I said, ‘’Wow, women get asked all the time’’. You know, I bring as much to it as you can. You know, I know what certain sectors of society need to help build the country after so that you have enduring peace. So that you have some resemblance of justice and equality.

One of the zones I did some work in was El Salvador, when the war ended, they did a peace treaty. I don’t know, it was maybe 38 or 40 pages. 70 or 80 percent of that treaty dealt only with separating the two warren sites, taking away the weapons of the two warren sites, blah blah blah, rules about the opposition, and at the end there were a few pages left that said ‘’And then we will worry about the socio-economic issues that led to the war’’. El Salvador today has been of the most dangerous countries in Central America, you know because they didn’t deal with the root cause of war and if you really want to deal with the root cause, you have to speak with the sectors of society beyond the men with the guns.

”There were times when I just wanted to quit. When I wanted to go move back to my state of Vermont which is on the Canadian border and frankly what I wanted to do was mock out horse stalls”

Jody Williams

Going to the question parallel to this, what remains the role of men in fighting against injustice? (both laugh) There’s definitely a lot to be done.

Yeah, a lot to be done. Have you heard of the term toxic masculinity?

Yes, of course.

Yes, I think men have to have the courage first to talk about toxic masculinity and how it affects them. I was a professor for a while and my students did a project and one of the projects was that they put up a big board on the campus and the title was ‘‘Say something about you and toxic masculinity: The impact it has on you’’ and the things that the young men said were amazing. You know because it was anonymous. Because they didn’t have to stand with their peers and say you know this really grosses me out. So they talked about the impact. And recognizing that you know the role we are forced to play in society is not exactly a choice.

You know men are supposed to be brave and rugged and all that shit. And once you can talk about them and think about, do I have to be this way? It’s hard to change if you don’t confront the things in yourself that are blocking change. So, I think for men to be able to make real efforts at change and see women and others as equals takes confronting your habit. You know, like ‘‘Why did I end up like this? Why do I have to pretend I’m willing to beat up anybody because I’m a man?’’ you know all that bullshit.

So, a lot of inner self-work.

Yeah, and it is hard work.

What were some of the struggles you have had to confront in your professional journey so far?

You know, I’m a normal human being. Sure, there were times when I just wanted to quit. When I wanted to go move back to my state of Vermont which is on the Canadian border and frankly what I wanted to do was mock out horse stalls. I wanted to mock the horse shit out of the stall because it was physical you know I didn’t have to think I just wanted to go be physical. Because I was sick of it all. But then you breathe deep and get back to work. I can’t imagine what I would have done if I really left activism. Cause that’s who I am.

In your panel, you described how impunity keeps criminals from going, and I was wondering if you could explain to our readers what that implies and what can be done to counteract it?

From time immemorial when women were raped for example, whether in war or just in general, the women are victimized, the men aren’t. And the women do nothing. I mean some idiot man rapes them and the person who is vilified and shamed is the woman. And because that continues to happen over generations and centuries and millennia, that’s impunity. If I can do whatever I want and can get away with it, that’s impunity. And if people can get away with criminality with absolutely having to pay nothing for, I don’t mean money, but time in jail, whatever, then it inspires other people to say ‘’Oh, hey, this dude did it, nothing happened. Maybe it interests me too’’.

You also explained it in the context of the war in Ukraine why some nations…

Well, when Putin came to power and he went back to Chechnya and kind of destroyed the country and then you know Moldova and Transnistria when he invaded parts of Georgia. He ended up on Georgian territory, nothing happened. When he supported Assad in Syria, nothing happened. When he went into Ukraine in 2014 and annexed Crimea and started the wars in the east, nothing happened.

If I were a man like Putin with megalomaniacal visions of myself as the rebuilder of ‘’Great Russia’’, if they didn’t do anything to me before, certainly I can invade the country. That’s impunity. If countries had done something in the beginning, he certainly wouldn’t have thought he could go on invading and stealing territory. That’s impunity. And it only stops when governments stand up against it. And too often they won’t because they have their own crimes that they have committed. So, it’s important that importunity is not let out to rain.

Now the last question is something you might have been asked multiple times before but for the sake of our readers, what piece of advice would you give to those who are just starting on their path towards activism?

Uhm, kind of the same thing I said to the audience today. I care about the things that I care about, the things that really get me upset. But I don’t expect everybody else to get upset by the things I get upset by. I wouldn’t mind if they did but you know for some people it is the environment, which is critical, of course, or LGBTQR+ or transgender or bad schooling. All of those are fundamentally important to creating societies and justice and peace and equality. So, if you get upset about x all I want you to do is get up off your ass, if you will, and do something about it.

Even volunteering a couple of hours, a week. You don’t have to change your life completely. Just care enough to give a few hours and be part of the change. Or in my view, you’re complacent with the problem. If you know about a problem and you do nothing to change it you’re complacent. People hate it when you say that.

For further inquiries and information on Jody Williams’ work please visit this website https://www.uh.edu/socialwork/about/faculty-directory/j-williams/

Made possible by 4GAMECHANGERS Festival that took place in Vienna between 15-17 May 2023. Inspiration, networking, and infotainment: the focal points of this year’s festival included Digitalization and Media, Female Power, Sustainability, Entrepreneurship, Working World & Education. As such individual panels and keynotes can still be viewed on the website at www.4gamechangers.io