Smart technologies make our lives easier: from smart maps that find the fastest way home through evening traffic to sprinklers that take light and plants into account before watering. One field of smart technology that is particularly fascinating is intelligent, artificial materials. They can be a starting point for further fields of use and new innovative products.

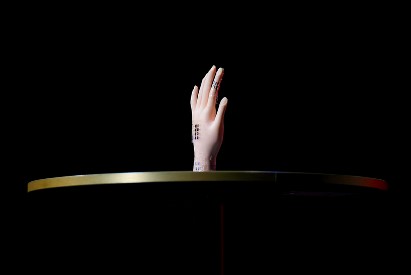

A proven expert in this field is TEDxVienna speaker Anna Maria Coclite. She is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Solid State Physics at the Graz University of Technology (TU Graz). Her research has been funded by various programs including the European Research Council (ERC) Starting Grant to fund her research on smart core-shell sensor arrays for artificial skins. Coclite and her research team created an artificial skin that cannot only measure pressure, or humidity, or temperature, but all three of them at the same time. Similar to our human skin but on an even finer level. While our human skin can “feel” objects that are one square millimeter small, the artificial skin could “feel” a thousand-times smaller objects like, for example, microorganisms.

At TEDxVienna’s 2022 main event “On the Rise” I had the chance to interview Anna. We talked about the research process, possible applications of the smart skin and her advice for young researchers.

What was your vision when you started the project?

I wanted to work on something that is not only studying a material but is something you can see, that does something. That’s why I thought, “Okay, let’s start working on sensors.” The sensor topic, I find it fascinating. I mean, it’s an interface between the environment and technology. Out of stimuli, out of temperature, out of humidity, you create something that can be measured.

In your experience what is the secret ingredient for the smart skin to turn out to be a success?

The materials that it is composed of. These materials really show the change of thickness that I was talking about during the talk.* That change of thickness is really, really big and it’s fast. It happens in a few milliseconds and this is the amazing thing about it. This is also the difference between it and the other artificial skins that exist already in other laboratories. They are all based on electronic materials or piezoelectric materials but not so much on stimuli responsive material. And that’s what we have and that’s what allowed us to have this multisensorial information.

*The hugely increased sensory resolution of the novel hybrid material is achieved by using a variety of nanorods on a surface. The “smart core” of these nanorods consists of a polymer which responds to temperature and humidity by expanding. The change in thickness of the polymer exerts pressure on its shell, i.e. the nanorods, which react sensitively to the pressure and in turn trigger stimuli. (Source: Barbara Gigler from TU Graz)

What was the most challenging moment during the research process?

Well, for sure getting the fundings. Because it was a large project, we absolutely needed a lot of money to pay the students, to pay for the equipment we needed. So I had to write a very big proposal. Big not in the sense of the number of pages, but a very complex proposal. I applied for the European Research Council grants, which are very competitive. They only fund high-risk/high-gain projects and if they like the project, they fund it with 1.5 million. That’s in fact the amount of money we needed. So that really was the most difficult part.

Are there many grants that would support such a big project then?

Not that many, no. Because when there is a lot of money involved, those are normally grants for consortiums. We were so much at the beginning that I could not really already form a consortium involving other universities and other groups. It was still “Let me try if it works,” you know. It was high-risk/high-gain: High-risk means that you are not sure when you write it, if it would really work at all.

So it was a really early stage, you had the idea and the theory around it and you wanted to explore and try something really new?

Exactly, yes, and that’s why I had to apply for that specific funding even though it was so competitive.

During your talk you mentioned different fields of application for smart skin. Which one, to you personally, is the most exciting and why?

Well, exciting – I don’t know. Prosthetic is the field that I would like this skin to be applied in as soon as possible. I find it fascinating that a prosthetic is already connected through a socket to the rest of the limb and that the brain can control the prosthetic. So there is already some kind of connection between the nerves and the artificial limb. I have the feeling that adding this artificial skin on top can just use the same electronic circuits that are already in the socket, which is connected to the rest of the limb. So I think it would give back useful information to the people who need the prosthetic.

You mentioned in your talk that the robots are overwhelmed by all the information. How do you think the experience will be for users of the prostheses if now all the new information from the skin comes in?

Probably it will still require some time to get used to. Of course, they need to learn how to move the prosthesis. This is also not automatic. For adding the artificial skin to the prosthesis I would need a lot of collaboration also with medical engineers, bio-engineers and so on. So this would be the next step. I don’t think that any of the applications would be immediate or have an immediate use. I think that there is a bit of research to go in the field. Now I could indeed make a consortium out of it and collaborate with other people that work in different fields to obtain a product.

I read that the production of the material can be easily integrated into existing production processes. How long do you estimate will it take for us to see your innovation in daily life?

This always depends a little bit. We need to find a field of application. So it could be applied on textile, it could be applied on, for example, robotics… Once we have found this field then I think the production would not require a lot of time, probably another five to ten years.

After so many years in research, what is your advice to young researchers or young people who would like to become scientists?

Take the challenge – this is my message.

Everything is a bit challenging: career in science is challenging, sometimes you have a great idea but it is challenging to find the money for testing it, sometimes the money arrives and sometimes it doesn’t and then you have to try again. For sure I advise them to take the challenge and be a bit resilient because things do not always happen immediately.

Do you have a kind of research bucket list and if yes, what is on it?

Of course I would like to become a full professor. I would also like for this project to arrive at a real product and commercialisation. So we are trying, for example, to open up our own start-up.

What keeps you excited about your job?

The research part and the interaction with my research students and my research group because they are all very smart people. Thanks to them we got to this point. So it’s never really me imposing them “You now work on this topic.” It is always a back and forth. I give an idea, they come back with “Oh actually, if we would do it this other way…” so they come back with their own ideas. It’s always a brainstorming interaction with them. This is the part that makes me the most enthusiastic.

On a broader note, what is on the rise in material science?

A lot of things are on the rise in material science. For sure smart sensors are now on the rise because they could be connected also with artificial intelligence and human-machine-interfaces. So this is absolutely a topic that is on the rise. But there are also others, for example materials for renewable energy are also very much on the rise.

If you could make a wish or a suggestion on how to optimize the research environment in Austria, would there be something on your mind?

The thing I really liked a lot when I was working at MIT was the possibility of using open laboratories. Laboratories where there are different types of equipment and people could just sign up and go there and use them. I didn’t find this in Austria, or at least in Graz there isn’t. On the other hand, I think this helps a lot with the research because you cannot have all the possible instruments in your laboratory. Especially when you work in a very interdisciplinary field. This for example would help a lot – doing some sharing.

If people can take away one thing from your talk or our readers from the interview, what should it be?

Challenging topics are a lot of fun!

Are you fascinated by the research of Anna Maria Coclite and want to learn more about its beginning? Then we can absolutely recommend you to watch her first TEDx Talk at TEDxGraz on the artificially recreation of everyday experiences.

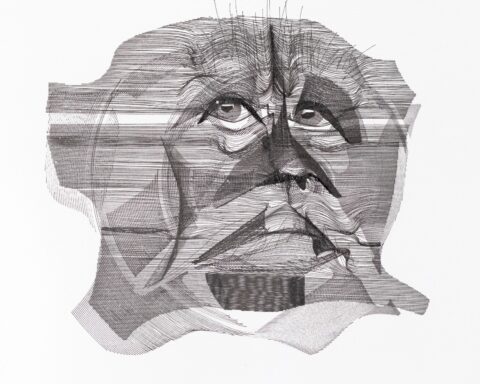

This article was proofread by Ipek Yilmaz. Cover image by Cherie Hansson on flickr.

What sets the smart skin developed by Anna Maria Coclite apart from other artificial skins in terms of its composition and sensing capabilities?