Increasing globalization over the last decades has revealed the need for new teaching methods that are tailored to the linguistic diversity often found in language classrooms. While multilingualism had been dismissed in the past and considered to be detrimental to the acquisition of the dominant language prevalent in a country, the knowledge and use of multiple languages are now highly welcomed and seen as a resource by many teachers in language learning. However, even though research has proven these practices to be highly beneficial for students, multilingual teaching approaches are still scarcely used in classrooms due to continual doubts and apprentice teachers not being sufficiently trained in implementing these methods.

One of the pedagogical practices that has emerged from researching multilingualism is translanguaging, which seeks to challenge previous models of bi- and multilingualism by privileging the learners’ “own dynamic linguistic and semiotic practices above the named languages of nations and states”. The term also describes the dynamic way multilingual speakers use their language repertoires depending on context and reflects their lived realities.

First introduced by Cen Williams to refer to “pedagogical practices in which English and Welsh were used for different activities and purposes”, the term ‘translanguaging’ was later picked up by Ofelia García, who is Professor Emerita in the Ph.D. programs of LAILAC (Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures) and Urban Education at the Graduate Center CUNY and has contributed extensive research in the domain of the education of bilinguals.

So, here are two reasons why translanguaging should be implemented in the language classroom and a few things teachers should keep in mind when using these methods.

Sociocultural Importance

Much of language learning in the past has been heavily influenced by the respective language’s cultural-political history and weaponized as a means to perpetuate hierarchies in certain countries. Because of this, marginalized languages that are often prevalent in a country alongside a dominant language are frequently neglected within institutions in order to maintain language purities, and subsequently run the risk of becoming extinct.

Other countries are rich in language diversity due to globalization, language contact or immigration, but consider only certain languages as prestigious and valuable, while others are not. As British linguist Li Wei explains, it is not possible to, for instance, view EMI (English medium instruction) simply as a medium of instruction, since it is “value-laden and ideologically driven”. Hence, one of the most important aspects of translanguaging is the way it validates the sociocultural diversity of language classrooms.

Rather than forcing students to adapt to a monolingual perspective of language learning for which they would have to leave their cultures and linguistic repertoires at the door, they are encouraged to “bring their whole selves into the classroom”. By bringing awareness to these sociocultural issues, institutions therefore not only honor students’ home languages, but also reinforce students’ identities.

This support is especially crucial, as it affirms and leverages their “lived-bilingualism”: many immigrant students or those who have immigrant parents make overt use of translanguaging in their everyday lives depending on the situation. An inclusive approach “emphasizes these flexible uses of students’ linguistic resources to make meaning of their lives and their complex communications” and can additionally help them build self-esteem.

While translanguaging could leverage students’ diverse and dynamic language practices in teaching and learning, it can also be highly beneficial for those students that grow up speaking one language only. Monolingual speakers are offered the opportunity to learn about different languages and are taught that other cultures need to be valued and are equally deserving of respect. This can strengthen intercultural bonds between the students and potentially prevent bullying or similar issues in the future.

Beneficial Effects on Students‘ Language Competence

As Wei mentions, expecting a pupil to learn the target language without making use of their entire language repertoire is like “tying one of their hands at the back or blindfolding one of their eyes and still expect them to do and see things as others do and see with two free hands and two open eyes”. Even so, language learning in the past usually prioritized and focused on the exclusive use of the target language, which is still the case in many language classes today.

For instance, in cases where a student’s native language is not considered to be a ‘prestigious’ language, the learner is often confronted with guilt and is reprimanded when making use of anything that is not the target language. Institutions that maintain such practices hold the conviction that multiple languages can disrupt the learning of the dominant language and be detrimental to their language competence in general.

This in turn keeps the linguistic proficiency of many students low, which can even prevent them from pursuing higher education or striving for more lucrative positions in their professional career. In support of a more effective and inclusive approach, many scholars such as Wei argue that translanguaging “brings out the multi-competence of all language learners and users” and can assist pupils in reaching their full potential. Canadian linguist Jim Cummins also posited that bilinguals’ language repertoires are not isolated systems within the mind of a speaker, but that knowledge and skills are interdependent.

Pupils’ home languages can and should therefore be used as a resource to facilitate this transfer and in turn further boost learning. This implies that multilinguals can build on their existing knowledge rather than push it aside, feel empowered instead of ashamed, and are able to acquire “comparable levels of competence in each language”, which could open many doors in the future.

Apart from developing competences in skills such as writing, reading, and speaking, translanguaging also enables more idea-generation, as it lifts inhibitions while talking and creates “opportunities for cross-linguistic comparisons”, in which language forms and systems of two languages are compared and contrasted. This metalinguistic awareness also leads to a deeper and fuller understanding of the subject matter, which creates “a bridge between the languages and content concepts”.

Applying Translanguaging within the Context of the Classroom

After having considered the number of benefits that come with translanguaging, the question arises as to how and when such important practices can be implemented in the language classroom. Especially in countries such as Austria, demands set by curricula and standardized testing make it immensely difficult, if not impossible to find the necessary time for meaningful activities that could potentially benefit individual learners.

Scholars such as Sara Vogel and Ofelia García have identified three core components of teachers’ translanguaging pedagogy: the first one, “Stance”, is the simple belief that educators should consider students’ language repertoires as a valuable resource that can be built upon. The second component, “Design”, describes the way language instruction is tailored in order to be purposeful, as well as relevant and beneficial to the needs of multilingual students. Lastly, “Shift” is the “ability to make moment-by-moment changes to an instructional plan based on student feedback”.

Moreover, translanguaging pedagogies should also be “purposefully designed and implemented”. Even though translanguaging occurs spontaneously in everyday communication of emergent bi- and multilingual students, teachers must develop strategies to “support student learning and metalinguistic awareness”. When employing these strategies, teachers must ensure that content knowledge which was acquired in one language is then consolidated in the other.

A great example of how this can be achieved is illustrated by a teacher’s anecdote, who decided to simply make micro-changes to her questions: instead of asking her students to think of how a certain phrase could be said in the target language, she reframed the question and asked if they could think of another way to express the sentence, which enabled students to make “cross-linguistic connections as they translated the text”.

Another crucial aspect is to promote interaction and inclusion and to make sure that learners also draw upon their linguistic resources when working in groups. One way to achieve this is to assign students into groups with peers based on linguistic proficiency and language background. Discussions and annotations can thus be held in their home languages, while at the same time making sure that all products are produced in the target language. Not only does such an approach increase interaction, it also gives learners “the sense that their home languages are a viable resource for achieving academically”.

Finally, scholars also repeatedly underline the importance of translanguaging pedagogies being enriching for all languages in a student’s linguistic repertoire, not just the target language. Translating is often mentioned as a useful way to “bridge” students’ developing skills. Drafts for a writing task, for instance, can be first written in a student’s home language, serving as “a scaffold for accessing their second, less proficient language” before writing the final product in the target language. Such an activity also represents an authentic purpose, since translating is something which is often part of learners’ “lived bilingualism”, as mentioned above.

Translanguaging pedagogies do not only provide language classrooms with incredibly useful methods to increase students’ language competences but are also necessary to ensure an inclusive classroom that values the sociocultural diversity of learners and their identities. Translanguaging can thus defy boundaries and disrupt hierarchies, as it emphasizes that strictly monolinguistic language teaching is obsolete and does not reflect the reality of today’s students.

Got interested? Check out this other article about language discrimination here.

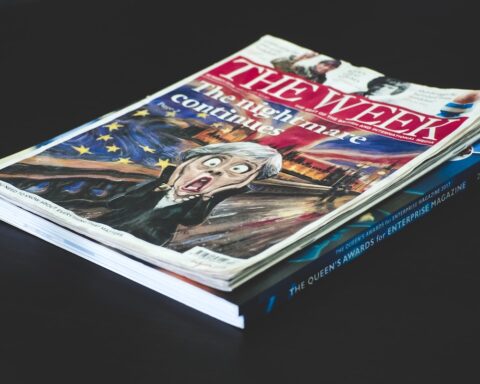

Header image from Unsplash

Anita, this is an amazing blog, thanks for sharing it. So down-to-earth!

What’s the reference for Wei please?

Harry

Hi Harry, thank you so much for your nice comment!

The reference for Wei is linked in the article the first time they’re mentioned!

Anita

Thanks for a well argued case for translanguaging. I fully agree with the benefits outlined by you. You have been looking at the use of translanguaging in the English or dominant language classroom. Translanguaging has also been applied in the content subject classroom. There is one caveat which you refer to – and that is the following sentence: ‘Discussions and anecdotes…whilst making sure that the final product is in the target language.’ Ultimately, in the content subject class, the student will be judged on the basis of his/her ability to respond in the target language to the questions, not in his/her home language.

In a context such as South Africa, translanguaging may, even if it is inadvertently, be used not to use the home language or the familiar language as a medium of instruction. Whilst I fully acknowledge the use of local or familiar or home language as a resource in a context where the medium

of instruction is a foreign or second or third language, it cannot compensate for the home language not being used as the medium of instruction – thus resulting in the hegemony of the target language not being challenged.

Thank you.