Art is full of possibilities. And of history. Recently, many countries have faced debates on the appropriateness of their monuments and statues. While this criticism is not a new phenomenon, current events make the effect of our historical past on the present more tangible for many people. Too seldom do we question our understanding of art and the way we interact with and display it. However, it is important to reconsider art and its impact in the context of history.

What is History?

In many history classrooms, this is one of the first questions that young students have to consider before opening their book at all. It is a difficult question to answer and it has been controversial for a long time. At first glance, history might simply consist of the chronological order of past events leading into the present. But many people have argued that this approach is too simplistic.

First, the historical knowledge that we are taught throughout our education is highly selective. This selectivity is necessary, because the entirety of recorded history is so extensive that it is impossible to include all of it in a lifetime’s study, let alone in basic education. However, it also means that many more marginalized historical perspectives are disregarded due to a bias in perspective. In schools, history is usually reduced to detailed information on the country you live in, as well as some more global historic events that are deemed beneficial to the understanding of that respective country’s history.

Therefore, we could define history as a collection of somewhat relevant, widely impactful factual events in chronological order taught by relevance to the place of origin. However, history is not simply that. In the best case, these factual events lay the groundwork of history as we know it. But the sources of information on the relevant events play an important role as well. These sources can consist of any form of record, such as writings, art, or oral tradition, among many other things.

Variability of Narrative

What defines our knowledge on these events is narrative. Narrative, in this context, describes the narrational focus and perspective that these stories have about historical events and people. Thus, the meaning of the saying: “History is written by the victors”, also historically ambiguous, becomes clearer. Though it has been used in various contexts, at its core it expresses the belief that dominant historical narratives are shaped by those who win wars and suppress other perspectives regarding the same event.

Thus, history does not only consist of the chronological order of events and facts, but also of the focus and lense of how the story is told. These stories are the essence of what we call history. Despite governing what schools teach us, it also exposes us to some narratives more than others.

Art in the Canon

In art, as in literature, music, and many other fields, the governing narratives are defined by a canon. The canon defines “the writings or other works that are generally agreed to be good, important, and worth studying”. These works are divided into time periods and categorized by techniques, regions of origin, and themes.

These paintings, statues, and architecture define our understanding of art and its implicated history. The works inside the canon are variable, especially within art history. There are a myriad of different artists that are included and excluded over time depending on exposure.

However, being excluded from the canon makes it immensely difficult for these artists and works to find a solid position within art history. One example of this is the art of many Black or Indigenous people in the United States. Looking back at world history, this is not surprising – people who were historically marginalized most likely didn’t have a high chance of being included in the canon of what was considered high art.

The Possibilities of History in Art

Shifting the Gaze, 2017

Oil on canvas

83 × 103 1/4 in. (210.8 × 262.3 cm)

Brooklyn Museum, William K. Jacobs Jr., Fund, 2017.34.

© Titus Kaphar

Regarding our history, we are constantly confronted with conflicting information and untimely representation. The statues, literature, and artworks that were and are still admired, often imply a certain erasure of those works that are not included in the canon.

However, the canon’s variable nature allows for changes in our understanding of it. The arts are highly interpretative, but it is art history that governs our focus within the works as well. So in order to work towards amending the reductive lense that art is viewed through and including more diverse works to broaden our repertoire of historical narratives, our focus must shift.

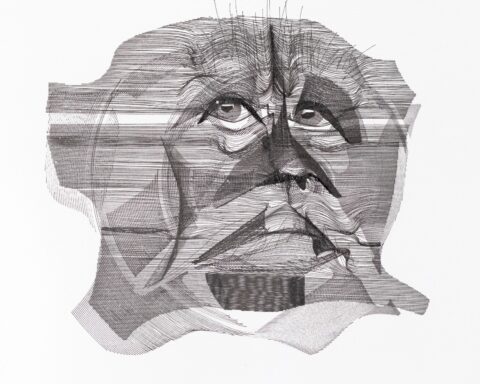

These shifts in focus are an essential factor in the work of artist Titus Kaphar. In his art, he explores the relationship between art history as it is taught today by schools, museums, and more, and African American presence. It is a reconsideration of prominent historical narratives in art. He shows us that art is not static. Not even a statue is simply an image frozen in time. Art has meaning and connections to each historical moment that it exists in and these might vary regarding time and place.

Kaphar makes use of this variability. “His practice seeks to dislodge history from its status as the “past” in order to unearth its contemporary relevance.” Kaphar’s performance and talk at a 2017 TED event in Vancouver, Canada visualizes his ideas and contextualizes his work with his own past and journey towards becoming an artist.

A New Lense

Kaphar’s argument is one against erasure. For the art canon and art history it is a shift of focus. This shift allows us to not only see history in art as a thing of the past, but to understand its impact on the present. Instead of erasing what was, we must try to amend historical injustice through actually doing the work and combine what we once knew with what we know now.

In regard to the question whether statues of controversial figures should remain in their place or be removed, Kaphar says: “[…] I actually think that that binary conversation is problematic. I think there is another possibility, and I think that possibility has to do with bringing in new work that speaks in conversation with this old work. It’s about a willingness to confront a very difficult past.”

Confrontation is difficult, but necessary. In an effort to understand and shift current social injustices, a reconsideration of history is inevitable. Art invites us to interact with history, avoid erasure and still allows us to shift our gaze. So the next time that we enter a museum or a gallery, maybe we can extend our view beyond the frame and read between the lines.