March heralds the beginning of a new semester for students in Austria, where we trade leisure activities for lecture halls and library desks. For me and others, this will be the last six months of our degrees, when we will scramble to complete theses, papers, presentations, while at the same time preparing to embrace new opportunities in the labor market. Some of us will decide to continue studying, taking on the mammoth task of a PhD perhaps and opening the doors to a future career in academia. This month we also celebrated International Women’s Day with the UN campaign slogan of I Am Generation Equality: Realizing Women’s Rights. With a report just released stating that nine out of ten people are biased against women, I wondered, how equal and inclusive of women is the wonderful world of academia?

A degree of confidence

The European Union reported that in 2017, there were 19.8 million tertiary students, 54% of them were women and for Masters degrees this rose to 57.1%. This is great. European women studying post-graduate degrees are achieving amazing things, right? Well, to a large extent yes, but participation drops off at the doctoral level, where women account for only 48%. This means there are fewer women than men on the path to an academic career in the first place, but what happens when they get there?

Barriers and bad reviews

Well, to progress upwards as an academic, you need to be recognized, your work needs to be peer-reviewed and published and it is extremely helpful if your work is cited. It sounds simple, but women in academia face multiple (un)conscious biases limiting their success. For instance, when women submitted papers under a double-blind review process – where both the author and the reviewer are unidentified – they were accepted more often than if the reviewer knew the author, like in single-blind reviews. For this reason, double-blind reviewing is considered the gold standard, and not just for women, but all underrepresented groups. This is good news, but as the authors of the double-blind study suggest, this type of review process doesn’t actually solve the problem of people having biases in the first place.

How easy is it to land a tenured position as a female academic? A well-known American study from 2003 analyzing Letters of Recommendation for positions in the field of medicine provides some clues. The study suggested that letters written for women, on average, focussed less on skills, abilities and excellence in their field of research than a male candidate. They were also on average shorter than those submitted on behalf of male candidates. What does this tell us? It suggests there are different variables impacting the hiring process for female academics compared to male academics, even if the procedure is essentially exactly the same. This is important because it could account for why in Europe in 2017, the majority of tertiary teaching staff (56.6% to be exact) were men.

Young and old

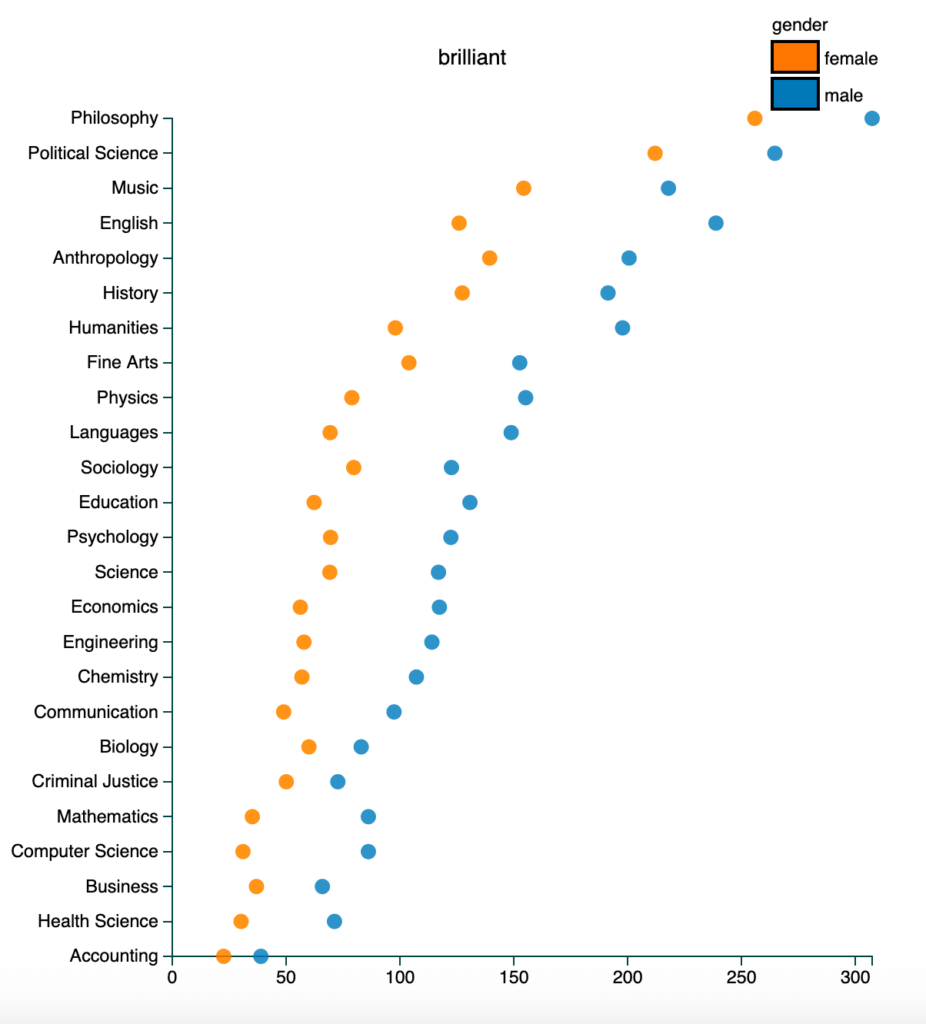

So you’ve proven yourself and landed the job. What happens when you start teaching the bright minds of the future? Similarly to the previous hiring example, evidence from the US suggests that student evaluations may also contain gendered biases. In one study, the same academic tutor presented with a male name in one online seminar, and with a female name in another. At the end of the course, students were asked to evaluate ‘both’ tutors. The students gave the ‘male’ tutor a higher score and were more likely to use positive descriptors, such as ‘brilliant’, than the ‘female’ tutor. While this study has been a little controversial in its design, you can check out another very interesting interactive visual tool which tracks the prevalence of certain keywords used in the US Rate My Professor webpage, a site where students can evaluate teaching staff. Have a look at the results for male and female professors across all disciplines when I type ‘brilliant’.

What does it all mean?

This all suggests that there is (un)conscious bias at all levels if you’re a female academic in the West. For even more examples, here is a great article written by some frustrated women. Another great overview about this and other issues is Invisible Women, from which this article takes a lot of inspiration. We also can’t forget that when we speak about ‘women’ in the data, we often don’t take into account race, sexual orientation, (dis)ability or other compounding factors which add layers of complexity and potential discrimination. This all matters because if women and other groups are underrepresented in academic fields (as in all areas of life), their needs are either willfully ignored or inadvertently overlooked in research outcomes. We only have to look at biases in medical research, leaving women sick and in pain to see the impact that a lack of diversity can have on our daily lives.

Make some change

We shouldn’t despair, but we can all commit to some strategic maneuvering to propel the thousands of qualified, intelligent, thoughtful, analytical and brilliant female and underrepresented academics further into the spotlight. How?

- If you’re a student and worried your seminars and lectures don’t draw on enough diverse authorship, mention it! Your professors should be happy to expose the class to a variety of positions and discuss these critically.

- If you’re writing something that others may read, try to cite as diversely as practicable. Every citation is a tiny advertisement for another person’s work.

- Praise the work of academics, professors and authors you are interested in and admire. Be intentional, seek out diversity in what you read, no matter the discipline, tell your friends and colleagues.

- Don’t be dissuaded if you want to enter academia and you’re a woman or member of an underrepresented group. Despite the barriers, you’re actually the answer! It’s a numbers game after all.

Photo by Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash